The power and purpose of photography

“The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” - Dorothea Lange

We are living in a perilous time. Humans have caused a biodiversity and climate crisis that continues to exacerbate. We need to act in order to save ourselves and life on Earth as we know it.

Action to save humanity comes in many forms and has to occur across our entire society. For people to best know how to act, they need education. The easiest way to educate adults is via the media - all forms of media.

And to get the right messages into the media, we need those that are trying to save the Earth to have their voices and their thoughts amplified. This is the job of writers, artists, journalists, filmmakers and photographers.

To capture the attention of people, and compel them to learn, and act - the role of the moving and still image has become crucial. The old adage of “a picture speaks a thousand words” remains as true today as it always was.

“Once you learn to care, you can record images with your mind, or on film. There is no difference between the two.” - Anonymous

Today, when we consider the word “imagery” we think of graphic design or photographs, or the work of cinematographers. Maybe also animation or cartoons. Perhaps other forms of visual art like projection and laser displays.

But the original, lasting human made imagery was made long before camera technology came to the world. It was scratched into wood and stone with sharp rocks, or mixtures of animal blood and sediment were smeared on cave walls. Some of this imagery remains visible today and still inspires and sparks wonderment.

“Every society needs sacred places. A society that cannot remember its past, and honour it, is in peril of losing its soul.” - Vine Deloria Jr.

The fact we continue to visit these sites as tourists, as anthropologists, as philosophers - pays testament to their magnetism and their power. They spark questions that in many cases we can only wonder at - but most importantly they tell us stories from another time.

Despite the saturation of imagery we now experience, in tens of thousands of years, future populations will analyse and wonder at what remains of our imagery - of our stories.

Such is the power and impact of image making.

This essay will focus on the art and craft of photography and its place in raising awareness and creating positive change for society.

“There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment.” - Robert Frank

The first permanent photograph taken was in 1827. ‘View from the Window at La Gras’ by Nicephore Niepce was a history-making moment. The image is entirely forgettable, but the action of making it was revolutionary. The ability to phyically manifest a reproduction of a scene in two dimensions was a revelation - seemingly magical.

As an interplay between light, time and chemistry. The creation of a photograph really is a magical thing. Today that magic has been somewhat stifled by the ease of production, however when the true magic of photography happens, when an image so remarkable is made that it takes our breath away, a different type of magic happens.

This is the interaction and connection between the photographer and their subject.

Photographic technology evolved through various methods of emulsion activated metal plates to the more familiar film cameras and eventually as digital sensors. A good rundown of that evolution can be found here.

High quality and thoughtful photographic imagery can influence societal change. There is no movement or cause that needs powerful and purposeful imagery than the movement to save life on Earth.

Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it. - Mary Oliver

Images of nature in its glory are easy to come by today. A simple internet search or scroll on social media provides an endless supply of beautiful images. Entire online platforms are dedicated to celebrating our lives through photographs.

But what makes one photograph stand out from all the others?

Connection.

Connection between the photographer and their subject can only be made if the photographer enters the scene with an open heart and mind, that they pay attention to what the scene represents and let the subject's essence wash over them.

Only then will a photographer be equipped to tell the true story contained within the scene.

This commitment to understanding the subject of a photograph, no matter what the scene is or where it may be, is how powerful and useful imagery is created.

Photography for conservation isn’t a new concept and isn’t just about documenting what may be threatened. Photographers are needed to document the human movement behind a cause and every facet of the campaign. They are necessary to demonstrate the connection of humans to place and their photographs need to serve as the emotional tie-line between the viewer and the subject.

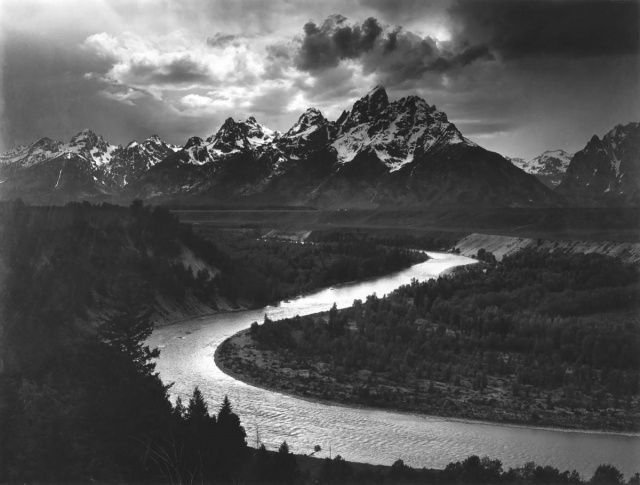

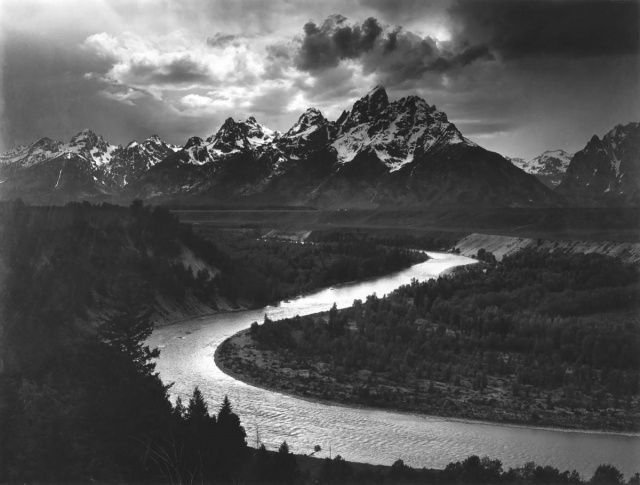

Ansel Adams was one of the first photographers to pour their creative energy into representing nature for the purposes of conservation. He is widely recognised as the “father” of landscape photography. Adams described himself as a photographer, lecturer and writer. It would perhaps be more accurate to say that he was simply a communicator.

In the 1950s and 1960s Nancy Newhall, an historian and administrator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Adams created a number of books and exhibitions of historic significance, particularly the Sierra Club’s ‘This is the American Earth’ (1960), which, along with Rachel Carson’s classic work ‘Silent Spring’, played a seminal role in launching the first broad-based citizen environmental movement.

Exposing the American citizens to the wonders of places such as Yosemite elicited a form of nationalism that had not been part of the modern American zeitgeist - a pride and love for the landscape of America, rather then the notions of Liberty and Freedom so closely tied to parochialism or nationalism. A love of country that until then was only known by the Native American peoples and a small number of explorers and settlers.

Adams’ black-and-white images were not “realistic” documents of nature. Instead, they sought an intensification and purification of the psychological experience of natural beauty. He created a sense of the sublime magnificence of nature that immersed the viewer in the emotional equivalent of wilderness, arguably more powerful than the actual thing.

And it is that legacy that survives today in photographers that put wildlife and wilderness conservation at the centre of their practice. The notion of transporting the viewer to a wild place, with an image so compelling they are stirred to want to care for it, without necessarily needing to visit.

The natural world has so many threats, they can be overwhelming, but by enlisting the skills and passions of image makers, community and environmental campaigners can begin stating their case, to raise awareness and maybe one image will win the campaign for them.

“Ask yourself: “Does this subject move me to feel, think and dream?” – Ansel Adams

One of Adams’ most influential images was taken in the Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. The photograph was part of the ‘National Parks Project’, instigated by the Department of the Interior.

The image is famed for its wonderful composition which invites the viewer to be swept through and immersed in the rich tapestry of the scene. A scene that emanates the power in the landscape, the forces that create it and the mystery imbued throughout.

Most importantly, this image is seared into the national consciousness. It is shorthand for nature protection, for national parks - and sparks national pride. This pride isn’t just because America contains scenes of immense beauty, but from the knowledge that Americans were smart enough to protect this place for future generations.

“A great photograph is one that fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed.” – Ansel Adams

The work of Adams, alongside others, helped protect vast tracts of land in national parks and started a global tradition amongst landscape photographers of working with conservationists to amplify their causes.

However, photographers have produced many other images throughout history that have created awe and wonder, but also outrage and horror.

The work of war photographers brought the realities of war into the daily lives of ordinary citizens and there are numerous images that have become ubiquitous, part of our everyday collective consciousness.

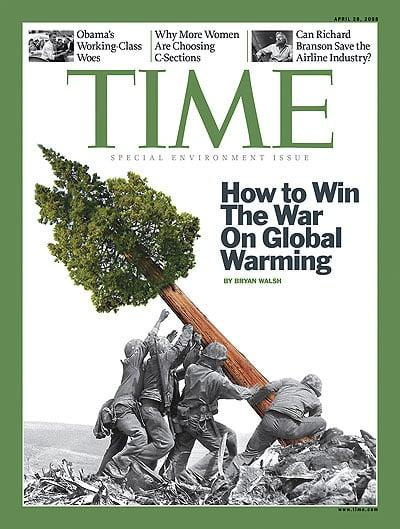

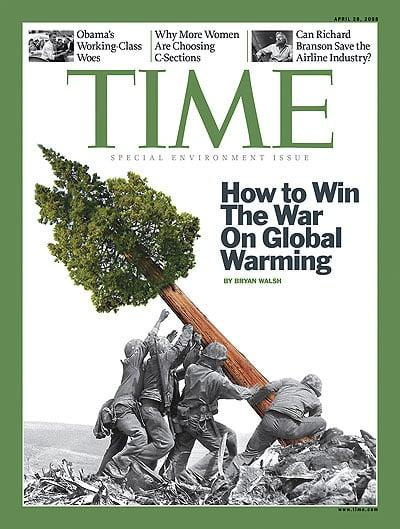

Captured after a crucial battle towards the end of World War II, this image came to symbolise more than the end of the war. It’s a lasting symbol of perseverance and camaraderie. It was published around the world within days of the battle, won a Purlitzer Prize and was recreated in the form of a statue as a national monument.

It is so recognisable within western culture, reenactments without soldiers or flags are often made in popular culture with no explanation required. It is recognised as the most parodied photograph in history.

The ‘War on Global Warming’ edition of Time magazine controversially created its own parody for a cover, such is the power of the image.

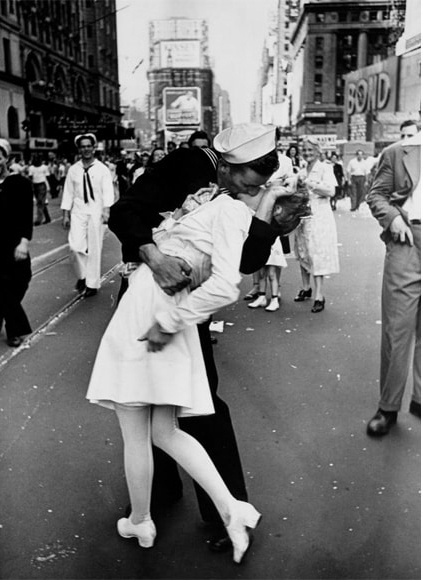

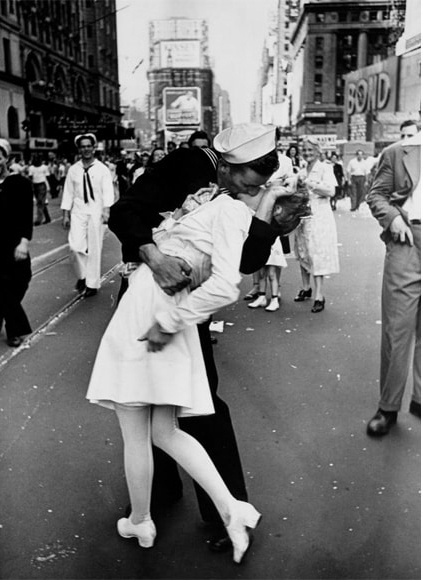

Sometimes an image from wartime can also inspire hope, exaltation, even joy.

Along with ‘Flag Raising on Iwo Jima’ this photograph, taken on Victory in Japan Day has been re-enacted countless times by happy couples visiting New York. The photograph is powerful because of the reckless abandon and joy contained in the moment.

Joy coming with the realisation the horror had finally ended.

These images are recognisable across generations of Americans, but wartime photography can also serve a vital need, more important than documenting the events. They can prevent wars beginning.

Some images, such as Nick Ut's 'The Terror of War', more commonly known as ‘Napalm Girl’ come to define an entire conflict, in this case, America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. It has since become a visual metaphor for the anti-war movement.

War cannot be justified when the results are so plainly horrific. 'The Terror of War' has been reproduced countless times to illustrate the futility of armed conflict.

Other equally horrific images play an important role in creating global awareness of an issue. They can be photographs of unspeakable war crimes, animal cruelty, human trafficking or acts of terror.

“It is an illusion that photos are made with the camera… they are made with the eye, heart and head.” - Henri Cartier-Bresson

Environmental activism has often been equated with war.

An environmental campaign is often a long, arduous affair with many highs and lows. There are minor victories and losses along the way, like battles in a war. There are rarely decisive moments of clear victory.

The ‘war’ of an environmental campaign is necessarily documented by photographers - with the resulting photographs playing a crucial role in the ‘battles’ along the way.

If there is a campaign to save a wild river from being dammed, it is essential photographers document the values that are threatened before they are lost. It is not enough to simply speak of these values, they must be on full display to as many people as possible.

The campaign to save that river relies on the public being educated on the issues at stake but even moreso, the campaign relies on affecting the hearts of the public and inspiring more to join the cause - hence the phrase “to affect hearts and minds.”

A good photograph touches the heart in an instant and plays on the mind, spurring action.

“The whole point of taking pictures is so that you don’t have to explain things with words.” - Elliott Erwitt

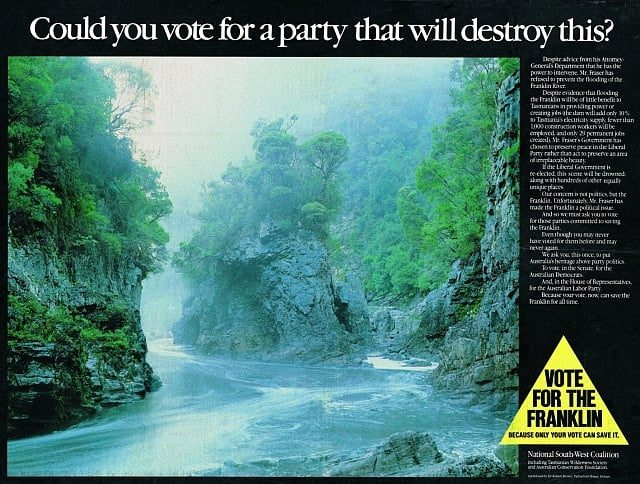

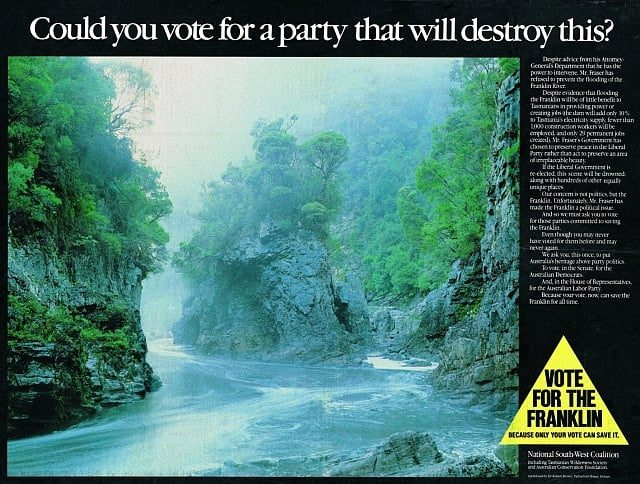

In Tasmania, Australia, a wild river was saved from damming, and many say it was saved by a single photograph.

That is a claim many campaigners will debate, but the campaign to save the Franklin River in Western Tasmania from a massive hydroelectricity project will forever be associated with this Peter Dombrovskis masterpiece.

The dreamlike image of a part of the Franklin River that was to be submerged under a watery impoundment gives an otherworldly, fantastic feeling of a place too precious to lose. During the Australian federal election campaign of 1983 the image was used in a national, full page newspaper advertisement by the Wilderness Society, with a simple question.

Could you vote for a party that will destroy this?

The Australian Labor Party, who campaigned on a platform of saving the river, won the election in a landslide. The river was saved and the photograph now has a place in Australian photographic and political history.

It was the deep and obvious connection Peter had formed with the Franklin River that resonated out of the image and affected a whole society.

The Australian Labor Party, who campaigned on a platform of saving the river, won the election in a landslide. The river was saved and the photograph now has a place in Australian photographic and political history.

It was the deep and obvious connection Peter had formed with the Franklin River that resonated out of the image and affected a whole society.

“When you go out there (into the wilderness), you don’t get away from it all, you get back to it all. You come home to what’s important. You come home to yourself.” - Peter Dombrovskis

By the time of the Franklin campaign win, Tasmania had become a global epicentre of environmental campaigning with landscape photographers and other artists front and centre. Peter Dombrovskis was one of the earliest ‘campaign photographers’ to gain attention for their work in nature, but he wasn’t the first.

The tradition of landscape photographers that contribute to environmental campaigns in Tasmania continues to this day in an unbroken line since the 1970’s, supporting campaigns to prevent logging and mining in takayna / Tarkine, industrial fish farming and to halt commercial development in national parks.

This image of a protester attempting to halt a tailings dam being constructed in pristine rainforest is a good example of a photographer working with campaigners to obtain a compelling image that campaigners can use on their social media or printed material.

As with photographing a revolution, a natural disaster or the events of war, nature conservation needs photojournalists as well as master landscape photographers. Every campaign needs someone on the ground, documenting the important moments as they occur.

When Brent Stirton chose to photograph rangers in the Congo, whose job was to protect mountain gorillas from poachers, he also found himself in a warzone and an area rich in valuable timber. Tensions were high and the inevitable tragedy occurred with seven gorillas murdered by illegal timber getters.

Brent’s photograph of the solemn procession of rangers recovering the body of a silverback gorilla is hard to look at, it’s shocking and it’s heartbreaking.

But when this photograph was published, it marked a turning point for gorilla protection. The world was outraged and the attention sparked further action to support rangers and save the gorillas.

Mountain Gorillas are still threatened, but it's arguable they are only surviving in the wild in Congo due to this photograph.

“In photography there are no shadows that cannot be illuminated.” - August Sander

Photography can assist many social movements as well as bookmark moments in history, where the collective memory of humanity has the same image seared into their minds.

A moment of futile resistance from one man against the irrepressible force of the Chinese military, taken during a crackdown on a protest movement in 1989, defines what is now known as the Tiananmen Square massacre, and is emblematic of resistance movements all over the world.

This single photograph will forever mark that moment in time.

Bearing witness to history making events is important, being there with a camera is vital.

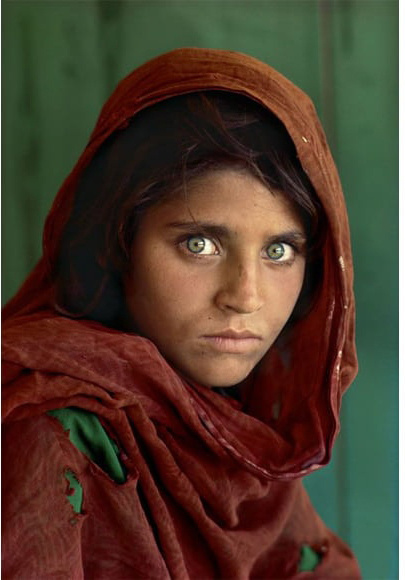

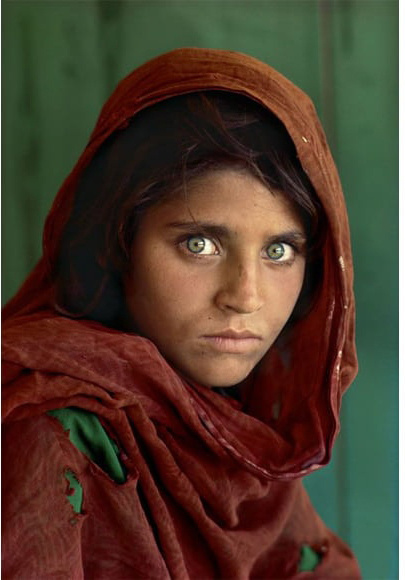

But a photograph can help us see far more than an historic event, a brutal crime or a magnificent landscape - it can help us see deep into the soul and into the history of a people.

“It’s one thing to make a picture of what a person looks like, it’s another thing to make a portrait of who they are.” - Paul Caponigro

This portrait of Sharbat Gula, who in 1984 was photographed while surviving in a refugee camp on the border with Pakistan, immediately evokes the modern story of Afghanistan. 50 years of war and displacement, foreign interference, subjugation of women and minorities, brutal dictatorships and the ongoing corruption of the innocence of children.

That one photograph can elicit so much speaks to the power of the image.

“A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart and leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it. It is, in a word, effective.” - Irving Penn

For a campaign to be effective, it must have imagery - it is for the campaign managers to think clearly about what images they need to raise attention, to maintain attention and to continually amplify their cause.

A team of passionate photographers is one of the first things all campaigns need. And a method to guide them on how to use their equipment to best effect is also vital.

We have prepared this guide to photography for grassroots community campaigners to make the most of the equipment and skills they have at hand.

“Taking an image, freezing a moment, reveals how rich reality truly is.” - Anonymous

Despite the seemingly impossible task of mobilising people to stand up for nature all over the globe we know it can be done.

Humankind has worked together to advance civil society and protect many special and sacred things and there is nothing more special, sacred or important as saving life on Earth.

Photographers will be there for every moment.

Dan Broun

Kuno Earth Media Centre Manager

“The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” - Dorothea Lange

We are living in a perilous time. Humans have caused a biodiversity and climate crisis that continues to exacerbate. We need to act in order to save ourselves and life on Earth as we know it.

Action to save humanity comes in many forms and has to occur across our entire society. For people to best know how to act, they need education. The easiest way to educate adults is via the media - all forms of media.

And to get the right messages into the media, we need those that are trying to save the Earth to have their voices and their thoughts amplified. This is the job of writers, artists, journalists, filmmakers and photographers.

To capture the attention of people, and compel them to learn, and act - the role of the moving and still image has become crucial. The old adage of “a picture speaks a thousand words” remains as true today as it always was.

“Once you learn to care, you can record images with your mind, or on film. There is no difference between the two.” - Anonymous

Today, when we consider the word “imagery” we think of graphic design or photographs, or the work of cinematographers. Maybe also animation or cartoons. Perhaps other forms of visual art like projection and laser displays.

But the original, lasting human made imagery was made long before camera technology came to the world. It was scratched into wood and stone with sharp rocks, or mixtures of animal blood and sediment were smeared on cave walls. Some of this imagery remains visible today and still inspires and sparks wonderment.

“Every society needs sacred places. A society that cannot remember its past, and honour it, is in peril of losing its soul.” - Vine Deloria Jr.

The fact we continue to visit these sites as tourists, as anthropologists, as philosophers - pays testament to their magnetism and their power. They spark questions that in many cases we can only wonder at - but most importantly they tell us stories from another time.

Despite the saturation of imagery we now experience, in tens of thousands of years, future populations will analyse and wonder at what remains of our imagery - of our stories.

Such is the power and impact of image making.

This essay will focus on the art and craft of photography and its place in raising awareness and creating positive change for society.

“There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment.” - Robert Frank

The first permanent photograph taken was in 1827. ‘View from the Window at La Gras’ by Nicephore Niepce was a history-making moment. The image is entirely forgettable, but the action of making it was revolutionary. The ability to phyically manifest a reproduction of a scene in two dimensions was a revelation - seemingly magical.

As an interplay between light, time and chemistry. The creation of a photograph really is a magical thing. Today that magic has been somewhat stifled by the ease of production, however when the true magic of photography happens, when an image so remarkable is made that it takes our breath away, a different type of magic happens.

This is the interaction and connection between the photographer and their subject.

Photographic technology evolved through various methods of emulsion activated metal plates to the more familiar film cameras and eventually as digital sensors. A good rundown of that evolution can be found here.

High quality and thoughtful photographic imagery can influence societal change. There is no movement or cause that needs powerful and purposeful imagery than the movement to save life on Earth.

Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it. - Mary Oliver

Images of nature in its glory are easy to come by today. A simple internet search or scroll on social media provides an endless supply of beautiful images. Entire online platforms are dedicated to celebrating our lives through photographs.

But what makes one photograph stand out from all the others?

Connection.

Connection between the photographer and their subject can only be made if the photographer enters the scene with an open heart and mind, that they pay attention to what the scene represents and let the subject's essence wash over them.

Only then will a photographer be equipped to tell the true story contained within the scene.

This commitment to understanding the subject of a photograph, no matter what the scene is or where it may be, is how powerful and useful imagery is created.

Photography for conservation isn’t a new concept and isn’t just about documenting what may be threatened. Photographers are needed to document the human movement behind a cause and every facet of the campaign. They are necessary to demonstrate the connection of humans to place and their photographs need to serve as the emotional tie-line between the viewer and the subject.

Ansel Adams was one of the first photographers to pour their creative energy into representing nature for the purposes of conservation. He is widely recognised as the “father” of landscape photography. Adams described himself as a photographer, lecturer and writer. It would perhaps be more accurate to say that he was simply a communicator.

In the 1950s and 1960s Nancy Newhall, an historian and administrator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Adams created a number of books and exhibitions of historic significance, particularly the Sierra Club’s ‘This is the American Earth’ (1960), which, along with Rachel Carson’s classic work ‘Silent Spring’, played a seminal role in launching the first broad-based citizen environmental movement.

Exposing the American citizens to the wonders of places such as Yosemite elicited a form of nationalism that had not been part of the modern American zeitgeist - a pride and love for the landscape of America, rather then the notions of Liberty and Freedom so closely tied to parochialism or nationalism. A love of country that until then was only known by the Native American peoples and a small number of explorers and settlers.

Adams’ black-and-white images were not “realistic” documents of nature. Instead, they sought an intensification and purification of the psychological experience of natural beauty. He created a sense of the sublime magnificence of nature that immersed the viewer in the emotional equivalent of wilderness, arguably more powerful than the actual thing.

And it is that legacy that survives today in photographers that put wildlife and wilderness conservation at the centre of their practice. The notion of transporting the viewer to a wild place, with an image so compelling they are stirred to want to care for it, without necessarily needing to visit.

The natural world has so many threats, they can be overwhelming, but by enlisting the skills and passions of image makers, community and environmental campaigners can begin stating their case, to raise awareness and maybe one image will win the campaign for them.

“Ask yourself: “Does this subject move me to feel, think and dream?” – Ansel Adams

One of Adams’ most influential images was taken in the Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. The photograph was part of the ‘National Parks Project’, instigated by the Department of the Interior.

The image is famed for its wonderful composition which invites the viewer to be swept through and immersed in the rich tapestry of the scene. A scene that emanates the power in the landscape, the forces that create it and the mystery imbued throughout.

Most importantly, this image is seared into the national consciousness. It is shorthand for nature protection, for national parks - and sparks national pride. This pride isn’t just because America contains scenes of immense beauty, but from the knowledge that Americans were smart enough to protect this place for future generations.

“A great photograph is one that fully expresses what one feels, in the deepest sense, about what is being photographed.” – Ansel Adams

The work of Adams, alongside others, helped protect vast tracts of land in national parks and started a global tradition amongst landscape photographers of working with conservationists to amplify their causes.

However, photographers have produced many other images throughout history that have created awe and wonder, but also outrage and horror.

The work of war photographers brought the realities of war into the daily lives of ordinary citizens and there are numerous images that have become ubiquitous, part of our everyday collective consciousness.

Captured after a crucial battle towards the end of World War II, this image came to symbolise more than the end of the war. It’s a lasting symbol of perseverance and camaraderie. It was published around the world within days of the battle, won a Purlitzer Prize and was recreated in the form of a statue as a national monument.

It is so recognisable within western culture, reenactments without soldiers or flags are often made in popular culture with no explanation required. It is recognised as the most parodied photograph in history.

The ‘War on Global Warming’ edition of Time magazine controversially created its own parody for a cover, such is the power of the image.

Sometimes an image from wartime can also inspire hope, exaltation, even joy.

Along with ‘Flag Raising on Iwo Jima’ this photograph, taken on Victory in Japan Day has been re-enacted countless times by happy couples visiting New York. The photograph is powerful because of the reckless abandon and joy contained in the moment.

Joy coming with the realisation the horror had finally ended.

These images are recognisable across generations of Americans, but wartime photography can also serve a vital need, more important than documenting the events. They can prevent wars beginning.

Some images, such as Nick Ut's 'The Terror of War', more commonly known as ‘Napalm Girl’ come to define an entire conflict, in this case, America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. It has since become a visual metaphor for the anti-war movement.

War cannot be justified when the results are so plainly horrific. 'The Terror of War' has been reproduced countless times to illustrate the futility of armed conflict.

Other equally horrific images play an important role in creating global awareness of an issue. They can be photographs of unspeakable war crimes, animal cruelty, human trafficking or acts of terror.

“It is an illusion that photos are made with the camera… they are made with the eye, heart and head.” - Henri Cartier-Bresson

Environmental activism has often been equated with war.

An environmental campaign is often a long, arduous affair with many highs and lows. There are minor victories and losses along the way, like battles in a war. There are rarely decisive moments of clear victory.

The ‘war’ of an environmental campaign is necessarily documented by photographers - with the resulting photographs playing a crucial role in the ‘battles’ along the way.

If there is a campaign to save a wild river from being dammed, it is essential photographers document the values that are threatened before they are lost. It is not enough to simply speak of these values, they must be on full display to as many people as possible.

The campaign to save that river relies on the public being educated on the issues at stake but even moreso, the campaign relies on affecting the hearts of the public and inspiring more to join the cause - hence the phrase “to affect hearts and minds.”

A good photograph touches the heart in an instant and plays on the mind, spurring action.

“The whole point of taking pictures is so that you don’t have to explain things with words.” - Elliott Erwitt

In Tasmania, Australia, a wild river was saved from damming, and many say it was saved by a single photograph.

That is a claim many campaigners will debate, but the campaign to save the Franklin River in Western Tasmania from a massive hydroelectricity project will forever be associated with this Peter Dombrovskis masterpiece.

The dreamlike image of a part of the Franklin River that was to be submerged under a watery impoundment gives an otherworldly, fantastic feeling of a place too precious to lose. During the Australian federal election campaign of 1983 the image was used in a national, full page newspaper advertisement by the Wilderness Society, with a simple question.

Could you vote for a party that will destroy this?

The Australian Labor Party, who campaigned on a platform of saving the river, won the election in a landslide. The river was saved and the photograph now has a place in Australian photographic and political history.

It was the deep and obvious connection Peter had formed with the Franklin River that resonated out of the image and affected a whole society.

The Australian Labor Party, who campaigned on a platform of saving the river, won the election in a landslide. The river was saved and the photograph now has a place in Australian photographic and political history.

It was the deep and obvious connection Peter had formed with the Franklin River that resonated out of the image and affected a whole society.

“When you go out there (into the wilderness), you don’t get away from it all, you get back to it all. You come home to what’s important. You come home to yourself.” - Peter Dombrovskis

By the time of the Franklin campaign win, Tasmania had become a global epicentre of environmental campaigning with landscape photographers and other artists front and centre. Peter Dombrovskis was one of the earliest ‘campaign photographers’ to gain attention for their work in nature, but he wasn’t the first.

The tradition of landscape photographers that contribute to environmental campaigns in Tasmania continues to this day in an unbroken line since the 1970’s, supporting campaigns to prevent logging and mining in takayna / Tarkine, industrial fish farming and to halt commercial development in national parks.

This image of a protester attempting to halt a tailings dam being constructed in pristine rainforest is a good example of a photographer working with campaigners to obtain a compelling image that campaigners can use on their social media or printed material.

As with photographing a revolution, a natural disaster or the events of war, nature conservation needs photojournalists as well as master landscape photographers. Every campaign needs someone on the ground, documenting the important moments as they occur.

When Brent Stirton chose to photograph rangers in the Congo, whose job was to protect mountain gorillas from poachers, he also found himself in a warzone and an area rich in valuable timber. Tensions were high and the inevitable tragedy occurred with seven gorillas murdered by illegal timber getters.

Brent’s photograph of the solemn procession of rangers recovering the body of a silverback gorilla is hard to look at, it’s shocking and it’s heartbreaking.

But when this photograph was published, it marked a turning point for gorilla protection. The world was outraged and the attention sparked further action to support rangers and save the gorillas.

Mountain Gorillas are still threatened, but it's arguable they are only surviving in the wild in Congo due to this photograph.

“In photography there are no shadows that cannot be illuminated.” - August Sander

Photography can assist many social movements as well as bookmark moments in history, where the collective memory of humanity has the same image seared into their minds.

A moment of futile resistance from one man against the irrepressible force of the Chinese military, taken during a crackdown on a protest movement in 1989, defines what is now known as the Tiananmen Square massacre, and is emblematic of resistance movements all over the world.

This single photograph will forever mark that moment in time.

Bearing witness to history making events is important, being there with a camera is vital.

But a photograph can help us see far more than an historic event, a brutal crime or a magnificent landscape - it can help us see deep into the soul and into the history of a people.

“It’s one thing to make a picture of what a person looks like, it’s another thing to make a portrait of who they are.” - Paul Caponigro

This portrait of Sharbat Gula, who in 1984 was photographed while surviving in a refugee camp on the border with Pakistan, immediately evokes the modern story of Afghanistan. 50 years of war and displacement, foreign interference, subjugation of women and minorities, brutal dictatorships and the ongoing corruption of the innocence of children.

That one photograph can elicit so much speaks to the power of the image.

“A good photograph is one that communicates a fact, touches the heart and leaves the viewer a changed person for having seen it. It is, in a word, effective.” - Irving Penn

For a campaign to be effective, it must have imagery - it is for the campaign managers to think clearly about what images they need to raise attention, to maintain attention and to continually amplify their cause.

A team of passionate photographers is one of the first things all campaigns need. And a method to guide them on how to use their equipment to best effect is also vital.

We have prepared this guide to photography for grassroots community campaigners to make the most of the equipment and skills they have at hand.

“Taking an image, freezing a moment, reveals how rich reality truly is.” - Anonymous

Despite the seemingly impossible task of mobilising people to stand up for nature all over the globe we know it can be done.

Humankind has worked together to advance civil society and protect many special and sacred things and there is nothing more special, sacred or important as saving life on Earth.

Photographers will be there for every moment.

You might like...

Nature as music

Natures Treasures

Albatross: a life at sea

Supergroms Cleanup at Alonnah

Newsletter

Sign up to keep in touch with articles, updates, events or news from Kuno, your platform for nature