Restoring urchin barrens in Sydney Harbour

Sea urchins have over-adapted to urbanisation, because we’ve removed predators from the food chain, things like Blue Gropers, which would typically clear large populations of urchins.

So in a particular area, they can just eat all the kelp, for example. So you get these areas called urchin barrens. They run out of food, the urchins will ultimately die, and you just get these clear patches of sand where they've been.

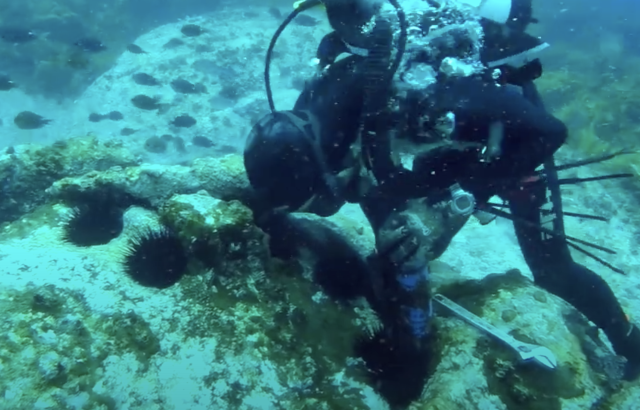

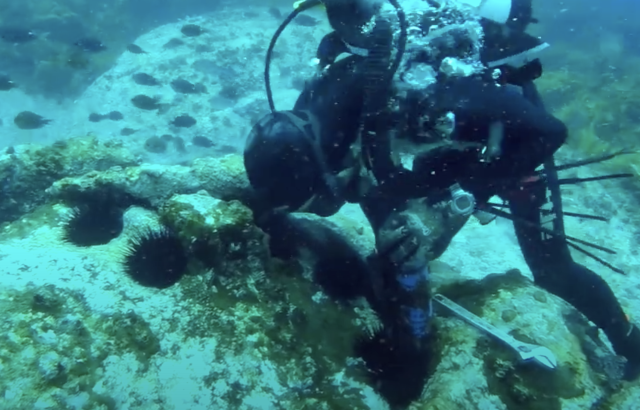

So in Sydney harbour, the way we're restoring kelp where it's been degraded, primarily through urchin predation, is simply removing the urchins. It is something we do by hand. If you've ever picked an urchin up - we don't recommend it! So the teams we have, they’ve got to have all the right gear, and it’s a slow process. The same team who are doing the seagrass restoration have Operation Crayweed, and they're also doing the kelp work for us in Sydney Harbour. This is based out of the University of New South Wales, with a collaboration from the University of Sydney.

They have got a trial area at Little Bay, which is near Maroubra. It's a reasonably small area. In three years they've been running that trial, they've removed over 7,000 urchins from the area. If you look at aerial photos, it has gone from being, patchy black bits of kelp you could only just see, to just entirely black - all you see is the kelp under the water. Kelp is an algae – so it does grow very quickly. This means that we're able to restore those types of environments way more quickly than we can with things like seagrasses.

Sydney Institute of Marine Science

Brett Fenton

Sea urchins have over-adapted to urbanisation, because we’ve removed predators from the food chain, things like Blue Gropers, which would typically clear large populations of urchins.

So in a particular area, they can just eat all the kelp, for example. So you get these areas called urchin barrens. They run out of food, the urchins will ultimately die, and you just get these clear patches of sand where they've been.

So in Sydney harbour, the way we're restoring kelp where it's been degraded, primarily through urchin predation, is simply removing the urchins. It is something we do by hand. If you've ever picked an urchin up - we don't recommend it! So the teams we have, they’ve got to have all the right gear, and it’s a slow process. The same team who are doing the seagrass restoration have Operation Crayweed, and they're also doing the kelp work for us in Sydney Harbour. This is based out of the University of New South Wales, with a collaboration from the University of Sydney.

They have got a trial area at Little Bay, which is near Maroubra. It's a reasonably small area. In three years they've been running that trial, they've removed over 7,000 urchins from the area. If you look at aerial photos, it has gone from being, patchy black bits of kelp you could only just see, to just entirely black - all you see is the kelp under the water. Kelp is an algae – so it does grow very quickly. This means that we're able to restore those types of environments way more quickly than we can with things like seagrasses.

Love what you're reading? Support Sydney Institute of Marine Science donate to support them now

Donate hereYou might like...

Sydney Harbour’s extraordinary marine biodiversity

Restoring Sydney Harbour’s seagrass

Saving White’s Seahorse

Living Seawalls for Sydney Harbour

Newsletter

Sign up to keep in touch with articles, updates, events or news from Kuno, your platform for nature