On the Shoulders of Giants Some thoughts on climbing on the Organ Pipes, Kunanyi

Kunanyi - Mount Wellington

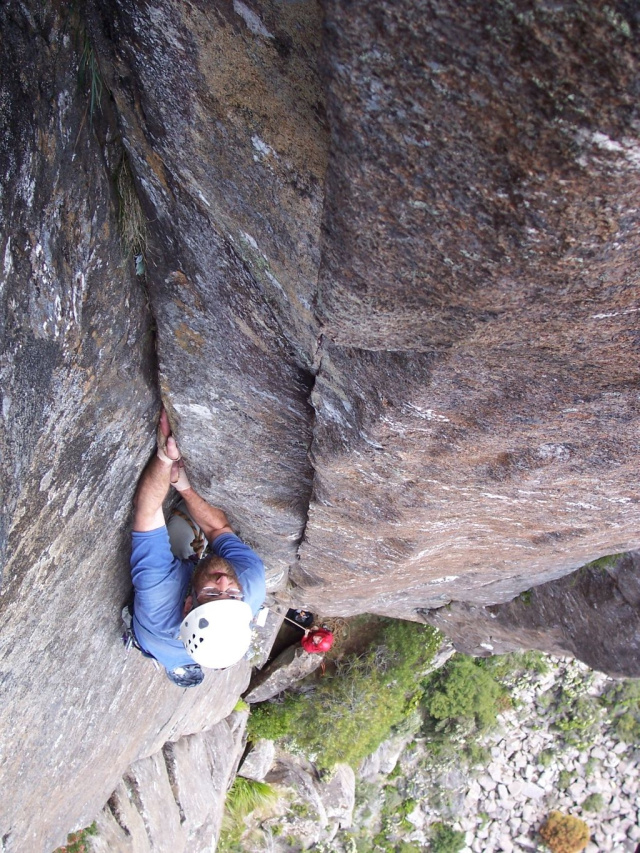

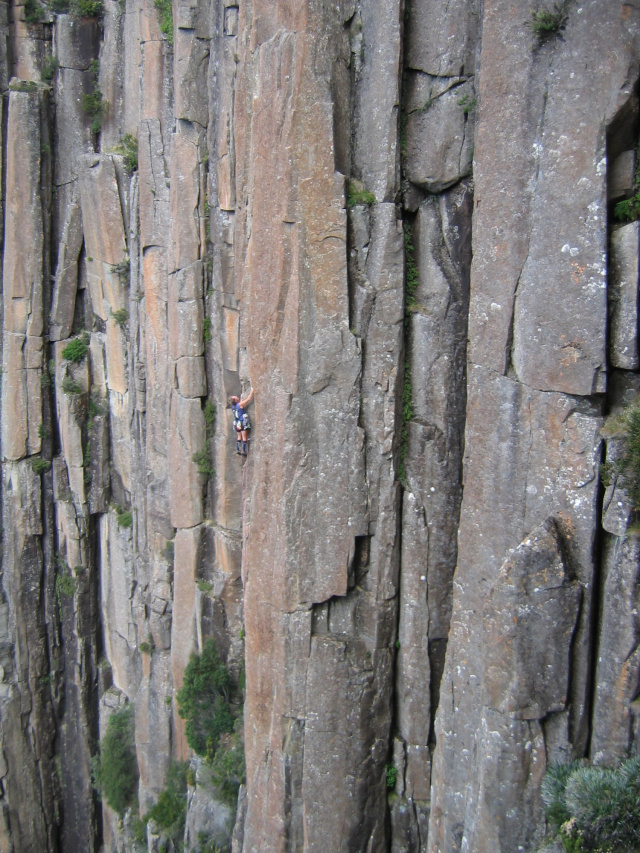

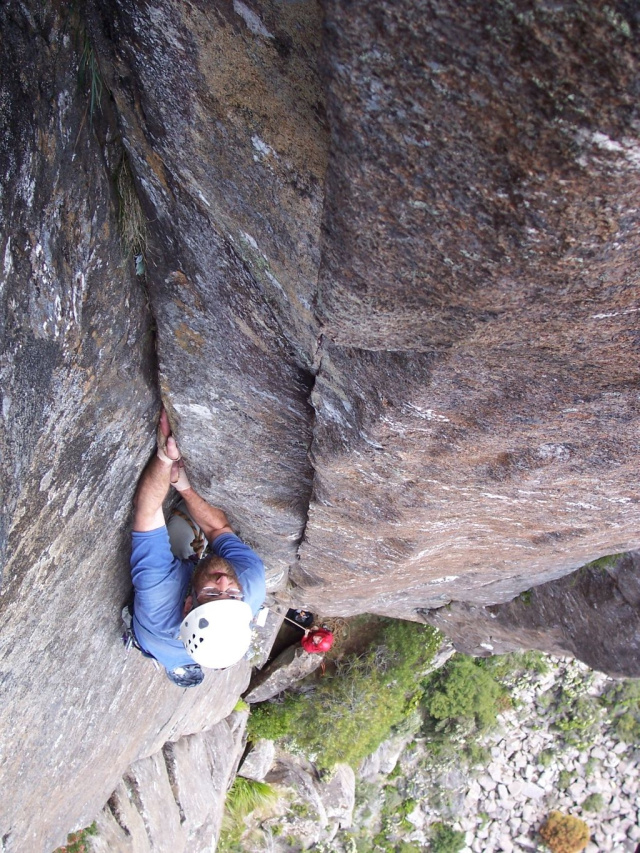

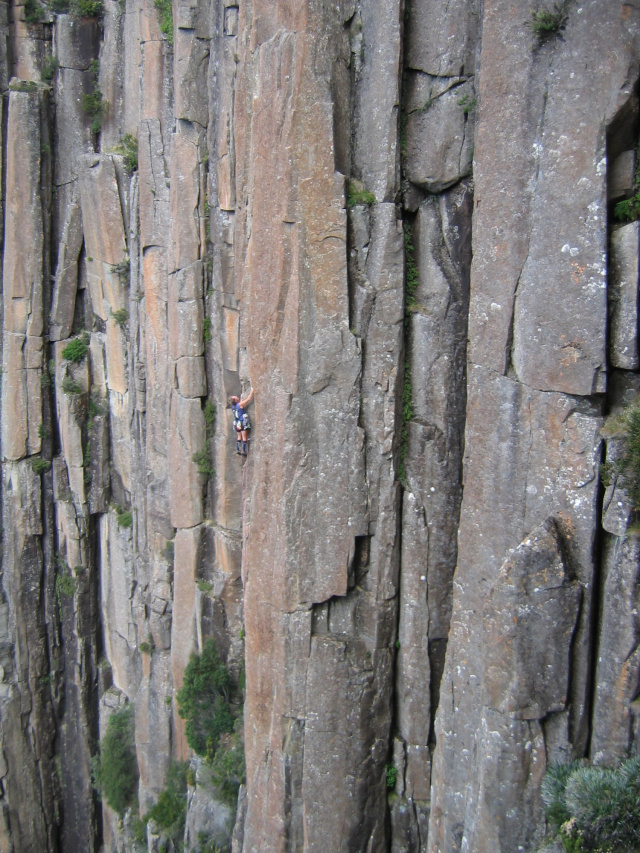

But for climbers, with their close intimacy with the vertical world, it actually never stops changing. They feel changes, smell falling rock and fear, hear the siren of deep play, see evolution in the mountain-scape: a flake of rock comes off here, a boulder crashes down there, a tree falls close by. Even a minor earth tremor would redesign the whole face of the Organ Pipes – what appears as a wall is in reality a massive collection of balanced, teetering fingers of rocks, “gendarmed” ridges defying the great leveller, gravity.

And the changes we do see are, in geological time at least, rapid and constant – we once simply pushed against one pinnacle high on the cliff only to see the rock launch down the slope like a toboggan, tonnes of rock careering down a gully, smashing trees and tracks with a roar. Another monster of a spire, loosened by the winter rains, toppled over carving a new way through the low bush, landing on the road and blocking traffic for days.

On close acquaintance it isn’t actually a wall at all but a labyrinth of gullies and pillars and ridges and spurs. Since the last great fire in 1967, the regrowth has been inexorably creeping up the weaknesses, reclaiming the crack lines with proto soil, returning beauty, complexity, and a variety of colour through flowers. The habitat for falcons and eagles had been reduced by fire to bare scree: photos show a veritable tsunami wave of plants now breaking up the steep ground, rising higher up the vertical cliff faces each passing year.

Kunanyi dominates our Hobart horizon and for many climbers it dominates their lives.

The early records of climbing in Tasmania as a recreational activity are scant. Newspaper accounts of mountaineering exploits in the European Alps had begun to appear in the colonial press in the mid nineteenth century and, following the acclaimed “first” rock climb on Napes Needle in the United Kingdom in 1886, rock climbing diverged from traditional mountaineering as a separate sport, with its own ethical rules, history and language. Interestingly, an early letter to the Hobart Mercury newspaper referred to an ascent on Van Diemen’s Buttress on the Organ Pipes on Kunanyi/Mt Wellington by R.D Power and F. Turner as far back as 1884, (two years prior to the Needles ascent!), while various reports at the time in the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail and the Mercury described serious rescues of “climbers” on Mt Wellington.

The first detailed account of a rock climb in Tasmania, (and possibly Australia) was actually the traverse of Cradle Mountain by the Austrian Malcher brothers in 1914, but between the two World Wars there was continuing media interest in climbing, both here and overseas. Locally, in August 1929, the Mercury reported the formation of the first Tasmanian specific rock-climbing club based in Hobart, with an aim to “explore the nooks and crevices of Mt Wellington”. Five years later, a young Max Angus, the distinguished Tasmanian artist, referred to the southern club in a letter to the Mercury concerning a particularly noteworthy accident on the Pipes. The newspaper even ran an article on a solo climb in 1934 by a visiting English pianist Yelland Richards (who died in a fall in Wales four years later), and another explaining the safe climbing methods in use at the time in Europe with an emphasis on the role of the leader – “the rule is, the leader must not fall”.

The first giants

But it wasn’t until well after the Second World War that we have any written records of any “club” as such. The first ascent of Australia’s most isolated and technically difficult mountain, Federation Peak, had been made by a mainland team in 1949, and Everest had finally been climbed in 1953 in time for the Coronation, creating much local jingoistic interest. It was no coincidence that around this time a new atmosphere of exploration and adventure swept the colony with a number of pioneering climbs across the state, including Skyline Minor on Kunanyi/Mt Wellington in 1958. Certainly, by 1960 there existed a loose, even anarchic, association of very tough, adventurous climbers and "hard" bushwalkers known collectively as the Van Diemen Alpine Club (VDC). It had no constitution, no rules and apparently never officially met, though paradoxically it had a bank account. Another talented group founded around this time in Hobart was the Tasmanian University Mountaineering Club (TUMC). Routes on the Pipes such as Pegasus, Sentinel Ridge, and the enigmatic Whose Route all date from this period.

From 1960 for the next two years, the TUMC and VDC were very active on the Mountain, although in those early days it was only a very small nucleus of local climbers, many of whom probably belonged to both groups. A number of these “locals” were originally from interstate and overseas, climbers who brought with them new gear, skills and ideas and who were influential in establishing new attitudes to climbing locally that reflected the revolution in standards and ethics particularly in the UK.

During this period at least 19 new routes were added to the Pipes, focusing on the soaring dolerite cracks and walls, but in early 1963, the VDC group suddenly dispersed. Most of the members left to go adventuring overseas or interstate – to NW Canada, European Alps, England, Canberra, France, New Guinea and NZ - and the VDC, such as it was, petered out.

The birth of the CCT

…to be replaced in 1965 by a new grouping in Hobart – the Climbers Club of Tasmania (CCT).

The roles of the new club back then were simple – it was where climbers could meet other climbers (no Facebook, X, Instagram or Zoom in those days), exchange route “beta” (information), organise weekly trips, arrange transport up or down the mountain and/or accommodation, share scarce gear, and provide training and advice to newbies. Monthly meetings were at the Victoria Tavern before moving to the Wheatsheaf in South Hobart for like-minded souls to brag and bullshit about their latest adventures.

The original membership was just 11, rising to 32 members by the end of the year. Most, but not all, were from the south, although an enigmatic reference in one of the club’s regular newsletters alluded to a “Launceston Mountaineering and Rescue Club” at about the same time, while another comment a year or so later on a club forming on the west coast indicates there may have been others …

From the outset the new club continued the traditions of the VDCs with the emphasis still very much on adventure climbing and still very much on mountaineering and the Mountain. There was a continuing emphasis on exploration including track cutting to the various buttresses as well as trips to isolated peaks and coastal cliffs.

Through the ‘60s and much of the ‘70s the CCT was generally an organised, close-knit group with regular club trips and activities, although there were the inevitable rumbles of dissatisfaction about certain hard-core members being too close-knit, and more than once an imminent total collapse of the club was predicted

Insights and Influencers

Not surprisingly, given our colonial history, the development of climbing on the Mountain was influenced by the changing scene in UK in particular, and international visitors to the state have had a significant input as well. One such early influencer was a young English immigrant, John Ewbank, who in 1968 gave club members a major boost in enthusiasm and skills with ascents of climbs like the Shield (20), Centaur (17) and the stunning crack line, Icarus (20). The near fatal accident to Phil Stranger in the same year on the Organ Pipes further galvanised the club into establishing a training program in rescue techniques for members, a need still recognised today.

By the beginning of 1969, the club membership had risen to 44. What is often forgotten is just how dramatically an increase in the standard of living and technological innovation have impacted local climbers over the decades. For example, back in the mid-1960s, communication was face to face at the pub or via the news sheets printed on a spirit duplicator; there were only line topos (many beautifully drawn by Peter Jackson), no GPS, no internet, few cameras – and of course, no mobile phones or access to any phone at all for most young climbers.

To help find climbs on the Organ Pipes and to share knowledge, the Climbers Club labelled every track and numbered every climb on the Mountain in white paint. You can still see one clearly at the base of Starseeker. Contact between climbers was via a hollow tree stump in Franklin Square in the centre of Hobart where climbers could leave messages midweek detailing the location and plans for a weekend of climbing delights for others to read and pass on. News of new routes, international developments, epics and accidents were all learned of via the monthly CCT newsletter, or from the handwritten guides, already well out of date before they could be circulated.

Transport up the mountain in those early days was by motor bike, car or bus, hitch hiking was relatively safe and still possible back then, and it was common practice for climbers, especially financially strapped students, to walk from say, Fern Tree to the Pipes and back again...

Another wave of change particularly through the 70s onwards was with the availability of better and more affordable equipment. By today’s standards, much of it what was available back then was still primitive and in short supply (climbers actually turned entrepreneurs in the 60s and brought in gear from UK for resale locally to club members in Hobart). Climbers walked and climbed in basketball shoes, with strong canvas uppers and soles of thick rubber, unsuitable for small holds on steep rock. On the upside, they did have good frictional adherence in the Pipes dolerite chimneys.

Common gear for a Pipe’s climb back in the late 50s was 40m of nylon hawser-laid rope, a hemp waistband (soon to be replaced by the ubiquitous swami belt), a couple of rope slings, a few Stubai mild steel pitons, a hammer and three or four steel karabiners. A few homemade pegs and wooden wedges were also used, and some still remain jammed deep in cracks and off widths on the Pipes. There were no technical cams then, nor polycentric hexes as we know them, or comfortable harnesses or light weight helmets or portable drills…

Hard trad climbing was in vogue on through the 70s, and standards improved out of sight as the potential of the new equipment was explored particularly on the Organ Pipes, where the focus was on new hard crack climbs. But it was in the mid-80s and early 90s that there was a particular period of rapid change in the climbing community, and this was ultimately to have a profound influence on climbing on the Pipes and the very future of the club.

Change in the Air

Activities on Kunanyi had actually surged in the mid-90s as the club welcomed in both the first wave of sport and gym climbers and boulderers, with a membership in 1994 of over 40 active climbers. The Club ran the first Tasmanian bouldering competition, a climbing writers’ competition, a photography competition, and numerous other social events

But the culture of the times was also a-changing. The mountain was increasingly a mecca for bushwalkers, tourists and visiting climbers, parking was a problem on busy summer days and tracks were barely coping. Climbers were now organising their own trips as transport became easier and cheaper (just look at the swish 4-wheel drives parked up at the Pipes nowadays). The club had always been Hobart centric (and white and male) but now there was a growing number of very talented and more diverse groups operating in the North and Northwest, and a re-energised Tas Uni club in the south.

For the first time there were commercial guided adventure walks up the more accessible gullies on the Mountain and professional climbing guides could be hired. Gear was now easily accessible (no need to trace round your footprint to send off to a supplier of rock boots in the UK) and was lighter, safer, stronger and much cheaper, route descriptions went online (over 400 different climbs of all difficulties) while rescue became the responsibility of the Police and SES.

The “Bolt Wars”

It was the advent of new bolting technology in late 70s and early 80s that saw the creation of the first bolted and mixed route (known generally as “sport”) climbing, with a concurrent rise in technical standards and significant tensions in the climbing community. (“Bolts” are small expansion bolts or glued in U-shaped staples which enabled climbers to safely climb near featureless walls and overhangs). The very talented young Turks of the day kicked open the sports climbing door and added the first bolts in Tassie to crags such as Sphinx Rock, Lost World, New World, and on the Pipes as well.

However, this also heralded an intense and divisive period of ethical debate around bolting and the provision of bolts and access/safety anchor chains by the club. Meetings could at times become heated and acrimonious, resulting in some people withdrawing from further leadership roles while others quit the club altogether to simply go climbing.

And by 1998 the last Krank circular lists a membership of just twelve climbers - the increasingly irrelevant club as we knew it had simply faded away.

Pressure for change

But soon there were new and growing pressures for the CCT to be resurrected…

Climbing had of course continued and there was unprecedented new route activity statewide. The numbers of climbers, and that includes everyone from the indoor gym tyro to the traditional mountaineer, had been rapidly increasing in the new millennia, and was no longer drawn simply from the youth of the Uni and Colleges. Now there are as many women as men, while family groups are joining the ranks along with older climbers (even very old climbers 😊). There was much more emphasis on bouldering (short technical free climbs on boulders) and on sports climbing than on traditional climbing; the environmental pressure of numbers was becoming obvious; access issues were leading to loss of venues for climbers; there were growing calls from the tourism sector and politicians for cable cars and environmentally degrading and inappropriate developments in our pristine bush landscape; and an increased sense of environmental stewardship was obvious as this new cohort of climbers took to the crags.

Rise of the Phoenix

And from the flames of necessity the phoenix of a newly fledged club was born.

This was to be a new and innovative model for a climbing club. Gone was the old activities focus, gone were regular meetings or shared club trips, membership was free, administration and meetings (other than an AGM) were minimised, and new routes and important issues were described, discussed, and debated online and recorded on Thesarvo website. Jon Nermut deftly drafted up four main areas of concern to form the club’s terms of reference viz: Access and Advocacy, Communication, Policy, Maintenance and Environmental Work, all of which have since proved crucial and necessary.

The new Kid on the Block

The CCT has played a vital role since the adoption of an official constitution in 2011. The active membership has dramatically increased, from the original small handful to over two hundred now in 2024 and rising, an obvious vindication of the effort of re-forming the club. Issues that have concerned members have been wide and varied, including dealing with management problems on the Organ Pipes; working with the Kunanyi/Mt Wellington Management Trust over signage, parking and track maintenance; partnering with a newly created spin off, Crag Care, and the Hobart City Council to ensure open access; consulting with the aboriginal community regarding heritage protection, and developing codes of conduct.

Politically, the Club has been providing policy advice to the Kunanyi Management trust and Government, and actively lobbying around the cable car controversies on the Mountain; establishing bolting standards and environmental guidelines particularly for Tasmanian Reserves and World Heritage areas; establishing and maintaining through Thesarvo web site a record of activity state wide; providing finance for retro bolting and safety lower-offs; developing a Crag Steward system to ensure that local access and environmental issues can be speedily dealt with; and organising the occasional social events/fund raisers, including a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the CCT with a mass traverse of Cradle Mountain. There are still accidents of course in such a popular climbing area, and we have a trained band of volunteers to deal with technical rescues, funded and equipped by public funding.

The mountain may always appear the same, that grey wall of vertical wilderness slumbering in deep time, still impassive and still oblivious, still beautiful and wild, but around it life is in continuous flux.

And the future?

The nature of our diverse sport continues to expand rapidly, and new political, economic and social processes are at play. We are experiencing a continuing growth in mobility with many, many more overseas and interstate visitors on our hill: there are very few cities with a rock-climbing paradise so close, a vertical challenge rearing a kilometre into the sky and only minutes from the city centre, a magnet for adventurers from around the world. Inevitably there will be more sports climbing and bolting issues, erosion, parking and toileting management problems, more climate related changes, the list goes on…but we are at least in a good space as a caring community to deal now with those concerns. And best of all, there is a new generation of educated climbers, bringing with them new energy, new expertise, and new knowledge.

So many adventures, so many adventurers, so little time.

Carpe diem.

Written by Tony McKenny.

Thanks to Bernard Lloyd, Al Adams, Neale Smith, Jimmy Duff, Jon Nermut, Hamish Jackson, Chris Lang, Phil Robinson, Gerry Narkowicz for their input.

Tony Mckenny

But for climbers, with their close intimacy with the vertical world, it actually never stops changing. They feel changes, smell falling rock and fear, hear the siren of deep play, see evolution in the mountain-scape: a flake of rock comes off here, a boulder crashes down there, a tree falls close by. Even a minor earth tremor would redesign the whole face of the Organ Pipes – what appears as a wall is in reality a massive collection of balanced, teetering fingers of rocks, “gendarmed” ridges defying the great leveller, gravity.

And the changes we do see are, in geological time at least, rapid and constant – we once simply pushed against one pinnacle high on the cliff only to see the rock launch down the slope like a toboggan, tonnes of rock careering down a gully, smashing trees and tracks with a roar. Another monster of a spire, loosened by the winter rains, toppled over carving a new way through the low bush, landing on the road and blocking traffic for days.

On close acquaintance it isn’t actually a wall at all but a labyrinth of gullies and pillars and ridges and spurs. Since the last great fire in 1967, the regrowth has been inexorably creeping up the weaknesses, reclaiming the crack lines with proto soil, returning beauty, complexity, and a variety of colour through flowers. The habitat for falcons and eagles had been reduced by fire to bare scree: photos show a veritable tsunami wave of plants now breaking up the steep ground, rising higher up the vertical cliff faces each passing year.

Kunanyi dominates our Hobart horizon and for many climbers it dominates their lives.

The early records of climbing in Tasmania as a recreational activity are scant. Newspaper accounts of mountaineering exploits in the European Alps had begun to appear in the colonial press in the mid nineteenth century and, following the acclaimed “first” rock climb on Napes Needle in the United Kingdom in 1886, rock climbing diverged from traditional mountaineering as a separate sport, with its own ethical rules, history and language. Interestingly, an early letter to the Hobart Mercury newspaper referred to an ascent on Van Diemen’s Buttress on the Organ Pipes on Kunanyi/Mt Wellington by R.D Power and F. Turner as far back as 1884, (two years prior to the Needles ascent!), while various reports at the time in the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail and the Mercury described serious rescues of “climbers” on Mt Wellington.

The first detailed account of a rock climb in Tasmania, (and possibly Australia) was actually the traverse of Cradle Mountain by the Austrian Malcher brothers in 1914, but between the two World Wars there was continuing media interest in climbing, both here and overseas. Locally, in August 1929, the Mercury reported the formation of the first Tasmanian specific rock-climbing club based in Hobart, with an aim to “explore the nooks and crevices of Mt Wellington”. Five years later, a young Max Angus, the distinguished Tasmanian artist, referred to the southern club in a letter to the Mercury concerning a particularly noteworthy accident on the Pipes. The newspaper even ran an article on a solo climb in 1934 by a visiting English pianist Yelland Richards (who died in a fall in Wales four years later), and another explaining the safe climbing methods in use at the time in Europe with an emphasis on the role of the leader – “the rule is, the leader must not fall”.

The first giants

But it wasn’t until well after the Second World War that we have any written records of any “club” as such. The first ascent of Australia’s most isolated and technically difficult mountain, Federation Peak, had been made by a mainland team in 1949, and Everest had finally been climbed in 1953 in time for the Coronation, creating much local jingoistic interest. It was no coincidence that around this time a new atmosphere of exploration and adventure swept the colony with a number of pioneering climbs across the state, including Skyline Minor on Kunanyi/Mt Wellington in 1958. Certainly, by 1960 there existed a loose, even anarchic, association of very tough, adventurous climbers and "hard" bushwalkers known collectively as the Van Diemen Alpine Club (VDC). It had no constitution, no rules and apparently never officially met, though paradoxically it had a bank account. Another talented group founded around this time in Hobart was the Tasmanian University Mountaineering Club (TUMC). Routes on the Pipes such as Pegasus, Sentinel Ridge, and the enigmatic Whose Route all date from this period.

From 1960 for the next two years, the TUMC and VDC were very active on the Mountain, although in those early days it was only a very small nucleus of local climbers, many of whom probably belonged to both groups. A number of these “locals” were originally from interstate and overseas, climbers who brought with them new gear, skills and ideas and who were influential in establishing new attitudes to climbing locally that reflected the revolution in standards and ethics particularly in the UK.

During this period at least 19 new routes were added to the Pipes, focusing on the soaring dolerite cracks and walls, but in early 1963, the VDC group suddenly dispersed. Most of the members left to go adventuring overseas or interstate – to NW Canada, European Alps, England, Canberra, France, New Guinea and NZ - and the VDC, such as it was, petered out.

The birth of the CCT

…to be replaced in 1965 by a new grouping in Hobart – the Climbers Club of Tasmania (CCT).

The roles of the new club back then were simple – it was where climbers could meet other climbers (no Facebook, X, Instagram or Zoom in those days), exchange route “beta” (information), organise weekly trips, arrange transport up or down the mountain and/or accommodation, share scarce gear, and provide training and advice to newbies. Monthly meetings were at the Victoria Tavern before moving to the Wheatsheaf in South Hobart for like-minded souls to brag and bullshit about their latest adventures.

The original membership was just 11, rising to 32 members by the end of the year. Most, but not all, were from the south, although an enigmatic reference in one of the club’s regular newsletters alluded to a “Launceston Mountaineering and Rescue Club” at about the same time, while another comment a year or so later on a club forming on the west coast indicates there may have been others …

From the outset the new club continued the traditions of the VDCs with the emphasis still very much on adventure climbing and still very much on mountaineering and the Mountain. There was a continuing emphasis on exploration including track cutting to the various buttresses as well as trips to isolated peaks and coastal cliffs.

Through the ‘60s and much of the ‘70s the CCT was generally an organised, close-knit group with regular club trips and activities, although there were the inevitable rumbles of dissatisfaction about certain hard-core members being too close-knit, and more than once an imminent total collapse of the club was predicted

Insights and Influencers

Not surprisingly, given our colonial history, the development of climbing on the Mountain was influenced by the changing scene in UK in particular, and international visitors to the state have had a significant input as well. One such early influencer was a young English immigrant, John Ewbank, who in 1968 gave club members a major boost in enthusiasm and skills with ascents of climbs like the Shield (20), Centaur (17) and the stunning crack line, Icarus (20). The near fatal accident to Phil Stranger in the same year on the Organ Pipes further galvanised the club into establishing a training program in rescue techniques for members, a need still recognised today.

By the beginning of 1969, the club membership had risen to 44. What is often forgotten is just how dramatically an increase in the standard of living and technological innovation have impacted local climbers over the decades. For example, back in the mid-1960s, communication was face to face at the pub or via the news sheets printed on a spirit duplicator; there were only line topos (many beautifully drawn by Peter Jackson), no GPS, no internet, few cameras – and of course, no mobile phones or access to any phone at all for most young climbers.

To help find climbs on the Organ Pipes and to share knowledge, the Climbers Club labelled every track and numbered every climb on the Mountain in white paint. You can still see one clearly at the base of Starseeker. Contact between climbers was via a hollow tree stump in Franklin Square in the centre of Hobart where climbers could leave messages midweek detailing the location and plans for a weekend of climbing delights for others to read and pass on. News of new routes, international developments, epics and accidents were all learned of via the monthly CCT newsletter, or from the handwritten guides, already well out of date before they could be circulated.

Transport up the mountain in those early days was by motor bike, car or bus, hitch hiking was relatively safe and still possible back then, and it was common practice for climbers, especially financially strapped students, to walk from say, Fern Tree to the Pipes and back again...

Another wave of change particularly through the 70s onwards was with the availability of better and more affordable equipment. By today’s standards, much of it what was available back then was still primitive and in short supply (climbers actually turned entrepreneurs in the 60s and brought in gear from UK for resale locally to club members in Hobart). Climbers walked and climbed in basketball shoes, with strong canvas uppers and soles of thick rubber, unsuitable for small holds on steep rock. On the upside, they did have good frictional adherence in the Pipes dolerite chimneys.

Common gear for a Pipe’s climb back in the late 50s was 40m of nylon hawser-laid rope, a hemp waistband (soon to be replaced by the ubiquitous swami belt), a couple of rope slings, a few Stubai mild steel pitons, a hammer and three or four steel karabiners. A few homemade pegs and wooden wedges were also used, and some still remain jammed deep in cracks and off widths on the Pipes. There were no technical cams then, nor polycentric hexes as we know them, or comfortable harnesses or light weight helmets or portable drills…

Hard trad climbing was in vogue on through the 70s, and standards improved out of sight as the potential of the new equipment was explored particularly on the Organ Pipes, where the focus was on new hard crack climbs. But it was in the mid-80s and early 90s that there was a particular period of rapid change in the climbing community, and this was ultimately to have a profound influence on climbing on the Pipes and the very future of the club.

Change in the Air

Activities on Kunanyi had actually surged in the mid-90s as the club welcomed in both the first wave of sport and gym climbers and boulderers, with a membership in 1994 of over 40 active climbers. The Club ran the first Tasmanian bouldering competition, a climbing writers’ competition, a photography competition, and numerous other social events

But the culture of the times was also a-changing. The mountain was increasingly a mecca for bushwalkers, tourists and visiting climbers, parking was a problem on busy summer days and tracks were barely coping. Climbers were now organising their own trips as transport became easier and cheaper (just look at the swish 4-wheel drives parked up at the Pipes nowadays). The club had always been Hobart centric (and white and male) but now there was a growing number of very talented and more diverse groups operating in the North and Northwest, and a re-energised Tas Uni club in the south.

For the first time there were commercial guided adventure walks up the more accessible gullies on the Mountain and professional climbing guides could be hired. Gear was now easily accessible (no need to trace round your footprint to send off to a supplier of rock boots in the UK) and was lighter, safer, stronger and much cheaper, route descriptions went online (over 400 different climbs of all difficulties) while rescue became the responsibility of the Police and SES.

The “Bolt Wars”

It was the advent of new bolting technology in late 70s and early 80s that saw the creation of the first bolted and mixed route (known generally as “sport”) climbing, with a concurrent rise in technical standards and significant tensions in the climbing community. (“Bolts” are small expansion bolts or glued in U-shaped staples which enabled climbers to safely climb near featureless walls and overhangs). The very talented young Turks of the day kicked open the sports climbing door and added the first bolts in Tassie to crags such as Sphinx Rock, Lost World, New World, and on the Pipes as well.

However, this also heralded an intense and divisive period of ethical debate around bolting and the provision of bolts and access/safety anchor chains by the club. Meetings could at times become heated and acrimonious, resulting in some people withdrawing from further leadership roles while others quit the club altogether to simply go climbing.

And by 1998 the last Krank circular lists a membership of just twelve climbers - the increasingly irrelevant club as we knew it had simply faded away.

Pressure for change

But soon there were new and growing pressures for the CCT to be resurrected…

Climbing had of course continued and there was unprecedented new route activity statewide. The numbers of climbers, and that includes everyone from the indoor gym tyro to the traditional mountaineer, had been rapidly increasing in the new millennia, and was no longer drawn simply from the youth of the Uni and Colleges. Now there are as many women as men, while family groups are joining the ranks along with older climbers (even very old climbers 😊). There was much more emphasis on bouldering (short technical free climbs on boulders) and on sports climbing than on traditional climbing; the environmental pressure of numbers was becoming obvious; access issues were leading to loss of venues for climbers; there were growing calls from the tourism sector and politicians for cable cars and environmentally degrading and inappropriate developments in our pristine bush landscape; and an increased sense of environmental stewardship was obvious as this new cohort of climbers took to the crags.

Rise of the Phoenix

And from the flames of necessity the phoenix of a newly fledged club was born.

This was to be a new and innovative model for a climbing club. Gone was the old activities focus, gone were regular meetings or shared club trips, membership was free, administration and meetings (other than an AGM) were minimised, and new routes and important issues were described, discussed, and debated online and recorded on Thesarvo website. Jon Nermut deftly drafted up four main areas of concern to form the club’s terms of reference viz: Access and Advocacy, Communication, Policy, Maintenance and Environmental Work, all of which have since proved crucial and necessary.

The new Kid on the Block

The CCT has played a vital role since the adoption of an official constitution in 2011. The active membership has dramatically increased, from the original small handful to over two hundred now in 2024 and rising, an obvious vindication of the effort of re-forming the club. Issues that have concerned members have been wide and varied, including dealing with management problems on the Organ Pipes; working with the Kunanyi/Mt Wellington Management Trust over signage, parking and track maintenance; partnering with a newly created spin off, Crag Care, and the Hobart City Council to ensure open access; consulting with the aboriginal community regarding heritage protection, and developing codes of conduct.

Politically, the Club has been providing policy advice to the Kunanyi Management trust and Government, and actively lobbying around the cable car controversies on the Mountain; establishing bolting standards and environmental guidelines particularly for Tasmanian Reserves and World Heritage areas; establishing and maintaining through Thesarvo web site a record of activity state wide; providing finance for retro bolting and safety lower-offs; developing a Crag Steward system to ensure that local access and environmental issues can be speedily dealt with; and organising the occasional social events/fund raisers, including a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the CCT with a mass traverse of Cradle Mountain. There are still accidents of course in such a popular climbing area, and we have a trained band of volunteers to deal with technical rescues, funded and equipped by public funding.

The mountain may always appear the same, that grey wall of vertical wilderness slumbering in deep time, still impassive and still oblivious, still beautiful and wild, but around it life is in continuous flux.

And the future?

The nature of our diverse sport continues to expand rapidly, and new political, economic and social processes are at play. We are experiencing a continuing growth in mobility with many, many more overseas and interstate visitors on our hill: there are very few cities with a rock-climbing paradise so close, a vertical challenge rearing a kilometre into the sky and only minutes from the city centre, a magnet for adventurers from around the world. Inevitably there will be more sports climbing and bolting issues, erosion, parking and toileting management problems, more climate related changes, the list goes on…but we are at least in a good space as a caring community to deal now with those concerns. And best of all, there is a new generation of educated climbers, bringing with them new energy, new expertise, and new knowledge.

So many adventures, so many adventurers, so little time.

Carpe diem.

Written by Tony McKenny.

Thanks to Bernard Lloyd, Al Adams, Neale Smith, Jimmy Duff, Jon Nermut, Hamish Jackson, Chris Lang, Phil Robinson, Gerry Narkowicz for their input.

You might like...

A precious mountain refuge for birdlife

Kunanyi "The Mountain" Hobart's special place

Forests critical for Climate and Biodiversity Protection

The importance of bush in an urban environment

Newsletter

Sign up to keep in touch with articles, updates, events or news from Kuno, your platform for nature