Hobart launch: Director Dr Phill Pullinger on the power of Kuno's mission

Introduction by Vanessa Bleyer, Kuno Director:

I first met Dr Pullinger in about the mid-zeros when we were working tirelessly to stop the proposed pulp mill in the Tamar Valley, and that's probably about all we knew about each other, because we were so determined to achieve our goal that we really only ever talked about how we were going to continue to stop this pulp mill. Which we did.

In many more recent years I've learned so much more about Phill. Now he's a general practitioner, kindly caring for people's health in our community. But for some reason, studying medicine wasn't enough for him. He also holds a Master's degree in economics and public policy. But he has been involved in protecting Nature his whole life. He led the Tarkine National Coalition's efforts to save a vast area of rainforest into takayna in the northwest of Tasmania.

He was the founding director of Environment Tasmania and he spearheaded the Tasmanian Forest Peace Agreement, which expanded Tasmania's World Heritage Area. And now I will pass over to him so he can tell us why he created Kuno - why the idea emanated in his mind and why this is something that we needed to do, not just for Australia, but for the world.

Over to you, Phill.

Dr Phill Pullinger: I want to start, or take us back 30 years, when Nelson Mandela gave a deeply divided South Africa his inaugural speech. It was a country that had been wrapped in turmoil and violence and deep divisions. During that speech he was looking for some themes that were unifying and universal, and that could rise above tribal divisions. This is what he said:

"Each time one of us touches the soil of this land we feel a sense of personal renewal. We're moved by a sense of joy and exhilaration when the grass turns green and the flowers bloom." - Nelson Mandela

If you're human and you've walked and you've breathed on this planet, then you'll be able to relate to the feeling Nelson Mandela is describing, no matter where you've come, the place and time, and that's because people need and are intimately connected with Nature. It's fundamental to our health, our well-being and our happiness. This need for connection with the Natural world, it's universal. It's hardwired into all of us through our evolutionary history. This connection with nature also shows that the more people are connected to Nature and the Natural world, the more they are aware of their own actions, and concerned for all living things.

This concern about the plight of all living things on this planet, and a desire to think hard about how we, at this point in time, can most effectively act to turn around that plight - that is at the heart of Kuno.

Each generation faces unique challenges, but we all, despite a different circumstance, have much to learn from those that have come before us. So the history of humans having concern about the Natural world and the impact that their own activities might have upon it is something that stretches back. The industrial revolution was an inflection point, an explosion of technology, industrial activity, human life expectancy, wealth and population put pressures on the Natural world that had never been seen before.

And people who knew and loved special places around the world could see those pressures and thought deeply about how they could act to address them.

A century ago, the Yosemite Valley was one of the many of Earth's natural wonders threatened by exploitation. John Muir and the campaigners for the Valley realised that most Americans had no idea about this place. They hadn't been there, they hadn't seen it, they hadn't walked in it, they hadn't camped in it. So what they needed to do was translate their love for that place to middle America. They did that through using the revolutionary technology of the time which was newspapers.

They beautifully wrote about their love for the Yosemite Valley and the people across the west coast in New York City began to fall in love with that place from a distance, through that translation of those people's love for that place.

The clincher was when they brought President Teddy Roosevelt to camp in the Valley. He came through a snowstorm and he came out transformed. He was lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by a hand. He went on to create hundreds of national parks and protected areas across that country.

Step forward several decades, and in the 1960s Rachel Carson was deeply concerned about the impact of pesticides on waterways, ecology and bird life. But she believed that the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and the realities of the universe around us, the less taste we shall have for destruction. She successfully reached out to millions about the wonder and plight of Nature, through beautiful writing, books and appearing on TV shows. She catalysed a generation of new environmental laws and campaigners.

Since that time, across every corner of the planet, from the Amazon to Kenya to Kakadu, generations of people who love their place, wrote books, field guides, put on slide nights, and told stories of Nature and Nature's plight, to translate their love for their corner of the planet into an effective effort to protect it.

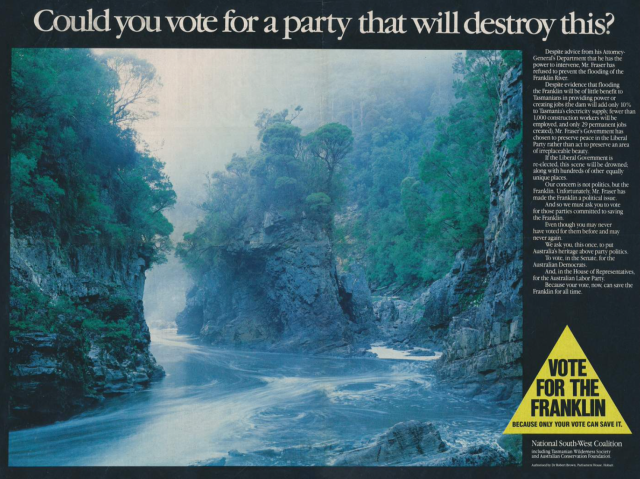

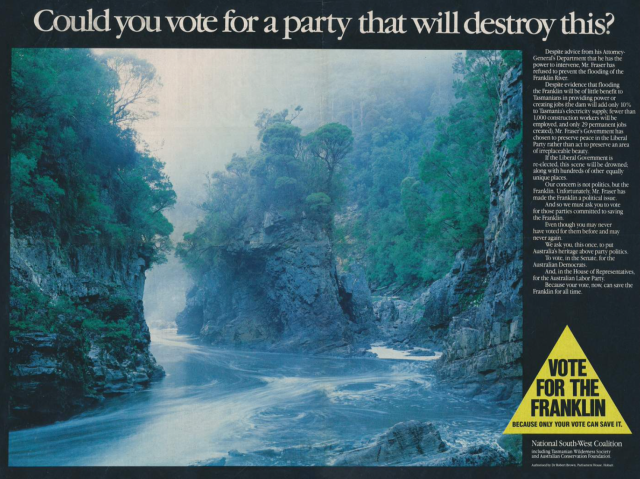

Close to home, in the 1980s, colour TV was spectacularly used to project stunning imagery of the south-west corner of Tasmania and the Franklin River into homes across Australia.

That use of that technology broadcasts the beauty of that place into a generation of Australian homes. Those Australians had grown up bushwalking and they knew and instinctively reacted to the imagery when they saw it.

In each case the pillar of protection was to connect people with Nature to activate their love of Earth, to tell powerful stories of nature and its plight and to effectively harness the most powerful technology of the time. Which brings us to today, and what we realised as we thought about what was needed at this particular point in time. The technologies that have totally revolutionised human society over the past two decades are mobile phones and platform technology.

In two short years, this technology has radically reshaped just about every sector of human society. As we did our research into this project, it was apparent that this technology hadn't effectively been applied to the challenge for humanity for this century, which was the Natural world.

As we researched, what we found first of all was that Nature online was a total mess. Lots of great information about the Natural world, lots of trails, lots of information, lots of different groups with bits and pieces of information but totally scattered in silos everywhere.

Another fun little thing that we realised, and we knew this from

our own experience, is that

there's also in every corner of the planet - despite the planet's plight - absolutely

extraordinary people and groups dedicating their lives to saving Nature. But these

people are often isolated, they're not connected to other groups, funding,

resources, networks and the training and skills they might need or benefit from to be

as impactful as they could.

So that's where we got to the idea for Kuno. We see the critical challenge for us is to reconnect people with Nature, to network and empower the people and groups across the planet that are acting for Nature, and through that effort, to scale the impact that those groups are having locally and globally for our planet.

Kuno is what's known as a two-sided platform. So, on one side of that platform is an amazing community of environment groups, writers, photographers, Naturalists, local experts and people that have extraordinary knowledge and commitment to the Natural world. At the other end of the the platform are those broader set of people who are seeking a connection with Nature.

What we seek to do with Kuno is to give that first group of people a platform and the tools, ability to gain funding, outreach networks and support to empower that work and make it have an impact.

And the second group of people - they're looking for stories, they're looking for knowledge, they're looking to visit beautiful places. They're looking to support the protection of the Amazon, but they don't know where and how. We want Kuno to be the tool that people can go to and find all that information beautifully and evocatively laid out for them.

That's obviously a massive task when you think about doing that on a global scale.

What we've chosen as our entry point is to focus on a few small local extraordinary corners of our planet and work with an amazing set of people and groups that live in those places and are committed to those places.

Kuno will beautifully present the ecology stories, Natural history and needs of those places, and bring those efforts of those groups to a broader audience.

Our key project has been Bruny Island, which we launched with the local community on Bruny Island last week. We've been partnering with the main environment groups on Bruny Island, an amazing network of photographers and experts and ecologists who are just contributing beautiful evocative information and stories of that place, why it's so special and how it can be protected.

Before I finish, I want to acknowledge that this project is built on deep foundations. So it's sought to learn deeply from all that those who have come before us, and grappled with the challenges facing our planet.

It has benefited greatly from the wisdom of co-founders Alec Marr and Rod West, both whom have brought a lifetime of thinking and work and experience in saving Nature to this project alongside an intellectual rigor and discipline sometimes to the point of driving me to desperation, of forcing us to not just straight jump straight into the next campaign or the next project but to first think deeply to get the foundations right.

To Vanessa, Dan, Peta, Raz, Jess, Javan, Shams and our incredible partner contributors and groups who we've worked with already, these people are absolutely inspiring. They've brought extraordinary skills, talents and passion to this project and it's an absolute joy and privilege to work alongside such wonderful people on such an important initiative.

And I have to say a very deep thanks to Katie, Rose and Bonnie for your patience with me as I've toiled over this labour of love over a few years. I really appreciate that. Your support has been crucial.

Lastly, I have to acknowledge that my understanding of where my own story of becoming an environmental campaigner started from, has changed during the course of this project. If you'd asked me a few years ago, I would have said that I became an activist when I stumbled across a logging coupe in the Tarkine rainforest as a university student, and threw myself into the campaign to protect it.

But one of the great insights that I've gained through this project has been, as I've worked with Dan and Peta and others, each of the people that we've been facilitating the stories of this project with, we've asked them where their love of Nature comes from.

There's some exceptions, but almost to a person they talk about their childhood. They talk about their experiences running around in the bush, not thinking about Nature, but just experiencing the joy of it. Running around, riding a bike, skidding stones, their mum nurturing their ability to spend time in the garden. This is something that just comes up again and again.

So for me, 45 years ago, my mum and dad - who are here, thank you mum and dad - they made a decision that they didn't want to bring kids up in the rat race in Sydney, and they moved to Tassie because they wanted to bring their kids up in the bush. And so when I saw that logging coupe, the reaction wasn't a head reaction, it was instinctive and it was emotional.

The big challenge that we face as a species is that half of humanity already, two-thirds by 2050, are going to live in cities. And this is driving people away from an understanding and connection with the natural world. And smartphone technology is accelerating that.

If this is not addressed, the long-term impacts of that phenomenon is just catastrophic, because people are going to lose that love and that connection with the Natural world that has been so fundamental to every effort to protect it. But there is hope.

I want to lean in and borrow a story. One of my favourite environmentalists is Wangari Maathai. She's the founder of the Green Belt movement in Kenya. She activated 30,000 rural Kenyans with an understanding that the loss of forests upstream of their rivers. was what was polluting their waterways, and she founded what they called the Green Belt.

Wangari Matai tells a story, about a hummingbird. She says there's a jungle that is caught on fire and there's a raging wildfire in the jungle. And all the jungle animals are collected around at the edge of the jungle, watching it, feeling helpless.

The lions, the elephants, the zebras. Meanwhile, there's this hummingbird zipping back and forth between the lake and the fire, going to the lake, collecting a few drops of water, going to the fire, dropping some water on the fire, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, furiously dropping this water on the fire.

And the other animals turn to the hummingbird and say, "What are you doing? What are you doing?" And the hummingbird says, "I'm doing what I can." I'm doing what I can.

So the challenge for us, for humanity, and the challenge that we're hoping that Kuno can make a dent into, is to light a spark of love for the Natural world in every single person we can. And when that spark is lit, we need to nurture that and gently nudge people towards action.

When people do take a decision to act, as extraordinary people in groups in every corner of our planet are doing, we need to provide them access to all the tools, skills, networks, support, training and resources and all strength to their collective arm in acting to save humanity and save our planet. This is the urgent task ahead of us and I hope you can join us as we do our best to take it on.

Phill Pullinger

Introduction by Vanessa Bleyer, Kuno Director:

I first met Dr Pullinger in about the mid-zeros when we were working tirelessly to stop the proposed pulp mill in the Tamar Valley, and that's probably about all we knew about each other, because we were so determined to achieve our goal that we really only ever talked about how we were going to continue to stop this pulp mill. Which we did.

In many more recent years I've learned so much more about Phill. Now he's a general practitioner, kindly caring for people's health in our community. But for some reason, studying medicine wasn't enough for him. He also holds a Master's degree in economics and public policy. But he has been involved in protecting Nature his whole life. He led the Tarkine National Coalition's efforts to save a vast area of rainforest into takayna in the northwest of Tasmania.

He was the founding director of Environment Tasmania and he spearheaded the Tasmanian Forest Peace Agreement, which expanded Tasmania's World Heritage Area. And now I will pass over to him so he can tell us why he created Kuno - why the idea emanated in his mind and why this is something that we needed to do, not just for Australia, but for the world.

Over to you, Phill.

Dr Phill Pullinger: I want to start, or take us back 30 years, when Nelson Mandela gave a deeply divided South Africa his inaugural speech. It was a country that had been wrapped in turmoil and violence and deep divisions. During that speech he was looking for some themes that were unifying and universal, and that could rise above tribal divisions. This is what he said:

"Each time one of us touches the soil of this land we feel a sense of personal renewal. We're moved by a sense of joy and exhilaration when the grass turns green and the flowers bloom." - Nelson Mandela

If you're human and you've walked and you've breathed on this planet, then you'll be able to relate to the feeling Nelson Mandela is describing, no matter where you've come, the place and time, and that's because people need and are intimately connected with Nature. It's fundamental to our health, our well-being and our happiness. This need for connection with the Natural world, it's universal. It's hardwired into all of us through our evolutionary history. This connection with nature also shows that the more people are connected to Nature and the Natural world, the more they are aware of their own actions, and concerned for all living things.

This concern about the plight of all living things on this planet, and a desire to think hard about how we, at this point in time, can most effectively act to turn around that plight - that is at the heart of Kuno.

Each generation faces unique challenges, but we all, despite a different circumstance, have much to learn from those that have come before us. So the history of humans having concern about the Natural world and the impact that their own activities might have upon it is something that stretches back. The industrial revolution was an inflection point, an explosion of technology, industrial activity, human life expectancy, wealth and population put pressures on the Natural world that had never been seen before.

And people who knew and loved special places around the world could see those pressures and thought deeply about how they could act to address them.

A century ago, the Yosemite Valley was one of the many of Earth's natural wonders threatened by exploitation. John Muir and the campaigners for the Valley realised that most Americans had no idea about this place. They hadn't been there, they hadn't seen it, they hadn't walked in it, they hadn't camped in it. So what they needed to do was translate their love for that place to middle America. They did that through using the revolutionary technology of the time which was newspapers.

They beautifully wrote about their love for the Yosemite Valley and the people across the west coast in New York City began to fall in love with that place from a distance, through that translation of those people's love for that place.

The clincher was when they brought President Teddy Roosevelt to camp in the Valley. He came through a snowstorm and he came out transformed. He was lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by a hand. He went on to create hundreds of national parks and protected areas across that country.

Step forward several decades, and in the 1960s Rachel Carson was deeply concerned about the impact of pesticides on waterways, ecology and bird life. But she believed that the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and the realities of the universe around us, the less taste we shall have for destruction. She successfully reached out to millions about the wonder and plight of Nature, through beautiful writing, books and appearing on TV shows. She catalysed a generation of new environmental laws and campaigners.

Since that time, across every corner of the planet, from the Amazon to Kenya to Kakadu, generations of people who love their place, wrote books, field guides, put on slide nights, and told stories of Nature and Nature's plight, to translate their love for their corner of the planet into an effective effort to protect it.

Close to home, in the 1980s, colour TV was spectacularly used to project stunning imagery of the south-west corner of Tasmania and the Franklin River into homes across Australia.

That use of that technology broadcasts the beauty of that place into a generation of Australian homes. Those Australians had grown up bushwalking and they knew and instinctively reacted to the imagery when they saw it.

In each case the pillar of protection was to connect people with Nature to activate their love of Earth, to tell powerful stories of nature and its plight and to effectively harness the most powerful technology of the time. Which brings us to today, and what we realised as we thought about what was needed at this particular point in time. The technologies that have totally revolutionised human society over the past two decades are mobile phones and platform technology.

In two short years, this technology has radically reshaped just about every sector of human society. As we did our research into this project, it was apparent that this technology hadn't effectively been applied to the challenge for humanity for this century, which was the Natural world.

As we researched, what we found first of all was that Nature online was a total mess. Lots of great information about the Natural world, lots of trails, lots of information, lots of different groups with bits and pieces of information but totally scattered in silos everywhere.

Another fun little thing that we realised, and we knew this from

our own experience, is that

there's also in every corner of the planet - despite the planet's plight - absolutely

extraordinary people and groups dedicating their lives to saving Nature. But these

people are often isolated, they're not connected to other groups, funding,

resources, networks and the training and skills they might need or benefit from to be

as impactful as they could.

So that's where we got to the idea for Kuno. We see the critical challenge for us is to reconnect people with Nature, to network and empower the people and groups across the planet that are acting for Nature, and through that effort, to scale the impact that those groups are having locally and globally for our planet.

Kuno is what's known as a two-sided platform. So, on one side of that platform is an amazing community of environment groups, writers, photographers, Naturalists, local experts and people that have extraordinary knowledge and commitment to the Natural world. At the other end of the the platform are those broader set of people who are seeking a connection with Nature.

What we seek to do with Kuno is to give that first group of people a platform and the tools, ability to gain funding, outreach networks and support to empower that work and make it have an impact.

And the second group of people - they're looking for stories, they're looking for knowledge, they're looking to visit beautiful places. They're looking to support the protection of the Amazon, but they don't know where and how. We want Kuno to be the tool that people can go to and find all that information beautifully and evocatively laid out for them.

That's obviously a massive task when you think about doing that on a global scale.

What we've chosen as our entry point is to focus on a few small local extraordinary corners of our planet and work with an amazing set of people and groups that live in those places and are committed to those places.

Kuno will beautifully present the ecology stories, Natural history and needs of those places, and bring those efforts of those groups to a broader audience.

Our key project has been Bruny Island, which we launched with the local community on Bruny Island last week. We've been partnering with the main environment groups on Bruny Island, an amazing network of photographers and experts and ecologists who are just contributing beautiful evocative information and stories of that place, why it's so special and how it can be protected.

Before I finish, I want to acknowledge that this project is built on deep foundations. So it's sought to learn deeply from all that those who have come before us, and grappled with the challenges facing our planet.

It has benefited greatly from the wisdom of co-founders Alec Marr and Rod West, both whom have brought a lifetime of thinking and work and experience in saving Nature to this project alongside an intellectual rigor and discipline sometimes to the point of driving me to desperation, of forcing us to not just straight jump straight into the next campaign or the next project but to first think deeply to get the foundations right.

To Vanessa, Dan, Peta, Raz, Jess, Javan, Shams and our incredible partner contributors and groups who we've worked with already, these people are absolutely inspiring. They've brought extraordinary skills, talents and passion to this project and it's an absolute joy and privilege to work alongside such wonderful people on such an important initiative.

And I have to say a very deep thanks to Katie, Rose and Bonnie for your patience with me as I've toiled over this labour of love over a few years. I really appreciate that. Your support has been crucial.

Lastly, I have to acknowledge that my understanding of where my own story of becoming an environmental campaigner started from, has changed during the course of this project. If you'd asked me a few years ago, I would have said that I became an activist when I stumbled across a logging coupe in the Tarkine rainforest as a university student, and threw myself into the campaign to protect it.

But one of the great insights that I've gained through this project has been, as I've worked with Dan and Peta and others, each of the people that we've been facilitating the stories of this project with, we've asked them where their love of Nature comes from.

There's some exceptions, but almost to a person they talk about their childhood. They talk about their experiences running around in the bush, not thinking about Nature, but just experiencing the joy of it. Running around, riding a bike, skidding stones, their mum nurturing their ability to spend time in the garden. This is something that just comes up again and again.

So for me, 45 years ago, my mum and dad - who are here, thank you mum and dad - they made a decision that they didn't want to bring kids up in the rat race in Sydney, and they moved to Tassie because they wanted to bring their kids up in the bush. And so when I saw that logging coupe, the reaction wasn't a head reaction, it was instinctive and it was emotional.

The big challenge that we face as a species is that half of humanity already, two-thirds by 2050, are going to live in cities. And this is driving people away from an understanding and connection with the natural world. And smartphone technology is accelerating that.

If this is not addressed, the long-term impacts of that phenomenon is just catastrophic, because people are going to lose that love and that connection with the Natural world that has been so fundamental to every effort to protect it. But there is hope.

I want to lean in and borrow a story. One of my favourite environmentalists is Wangari Maathai. She's the founder of the Green Belt movement in Kenya. She activated 30,000 rural Kenyans with an understanding that the loss of forests upstream of their rivers. was what was polluting their waterways, and she founded what they called the Green Belt.

Wangari Matai tells a story, about a hummingbird. She says there's a jungle that is caught on fire and there's a raging wildfire in the jungle. And all the jungle animals are collected around at the edge of the jungle, watching it, feeling helpless.

The lions, the elephants, the zebras. Meanwhile, there's this hummingbird zipping back and forth between the lake and the fire, going to the lake, collecting a few drops of water, going to the fire, dropping some water on the fire, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, furiously dropping this water on the fire.

And the other animals turn to the hummingbird and say, "What are you doing? What are you doing?" And the hummingbird says, "I'm doing what I can." I'm doing what I can.

So the challenge for us, for humanity, and the challenge that we're hoping that Kuno can make a dent into, is to light a spark of love for the Natural world in every single person we can. And when that spark is lit, we need to nurture that and gently nudge people towards action.

When people do take a decision to act, as extraordinary people in groups in every corner of our planet are doing, we need to provide them access to all the tools, skills, networks, support, training and resources and all strength to their collective arm in acting to save humanity and save our planet. This is the urgent task ahead of us and I hope you can join us as we do our best to take it on.

You might like...

Hobart launch: Director Alec Marr on seeing what's in front of us

Hobart launch: S. Group's Monica Plunkett and Javan Griffiths

Hobart launch: writer Helen Cushing on how to contribute to Kuno

Hobart launch: introducing Shams Uddin

Newsletter

Sign up to keep in touch with articles, updates, events or news from Kuno, your platform for nature