Adrift Among Canyons of Coral

A Parallel Universe

In it.

Suspended.

Adrift in a watery immensity.

Apparently accepted by the Underwater Society, whose members take no notice of us, we are snorkellers, quite an abundance of snorkellers, on a tourism mission, superficially at least.

A fringing reef such as Ningaloo is a coveted destination despite being remoter than most remote places on the planet. Remote here means 1,300 kilometres north of the remotest city in the world, which is Perth, Western Australia. Western Australia is enormous, mostly desert, full of startling geology, a multitude of unique plants and dens of hyper capitalism in the form of mines. I have visited a few choice pockets, where the geology and the plants and the vastness have coalesced in a magical formula equalling awe and wonder. The coastline is an extravagant 12,889 kilometres long, not counting islands: infinite scope for beauty, wildness and wayfinding.

Here I am, finding my way in the Cape Range National Park, a rugged peninsula where sprawling suburbs of red earth termite mounds populate the desiccated plains against the backdrop of a squat plateau, arid, unforgiving, cracked with shadowy gorges where rock wallabies and lizards shelter, while raptors drift like little clouds on currents of air, sweeping the sky, lazy and alert at the same time, seeing more than all the tourism efforts below reveal.

Evolving Into A Sea Creature

I am not adapted for underwater exploration, being of an earthy disposition. I love gardening, for example, and walking. For this moment I need evolutionary help. I need a new skin and webbed feet; I need a breathing tube and eye protection. The national park visitor’s centre has the answer, skipping millennia of genetic mutation. I hire a wetsuit, flippers, mask and snorkel – evolving into a sea creature costs $40 for two days.

Leading off the main artery, the peninsula is striated with short roads ending in car parks that feed you into walking tracks which in turn, deliver you to beaches, bays, rock platforms, fruit bats dangling in mangroves, lagoons, a bird hide, a turtle nesting site. Other short roads end with basic camping sites where tents have become a rare and endangered species, dwarfed by over-equipped mobile homes in denial about the notion of ‘basic’.

Having wrestled bodies into wetsuits in the Turquoise Bay carpark, Tim and I head to the beach, pilgrims from a faraway island lapped by the Southern Ocean, seeking absolution from the evils of our modern world, from news of wars and melting glaciers, extinctions and extractions, coral bleaching and immoral tyrannies, the daily diet of terror which lays waste our souls. Here, we will feed on something pure that should sustain us for a while when we return to buildings, carbon emissions, razed forests and farmed fields of poison.

The beach is peopled with fellow pilgrims, co-existing with mutual purpose. A toddler in a huge bucket at the seashore is contented in her own contained ocean. A tour group receives instructions from their guide. Face-down, bodies move around out there in the water, which laps around them with indifference, making room for everyone equally. The sun is watching, there are no clouds, a wind blows; it practically always blows.

"Here, we will feed on something pure that should sustain us for a while when we return to buildings, carbon emissions, razed forests and farmed fields of poison."

All Is Contained In The Massaging Sea

We walk south along the beach, that we may drift north with the current, among canyons of coral in the land of the USFA. Kitted out, we launch in. White sand and ripples, then dark patches of other stuff, and a few fish cruising these shallow outskirts before the reef proper. They know the way to somewhere meaningful I guess, or are they outliers pushing fluid boundaries because they can? Perhaps they are introverts who find reef society overcrowded, preferring some emptiness.

It’s so peaceful under water, where no-one talks and all is contained in the massaging sea.

My flippering feet push me beyond the shallows where fish society is busy on the reef, lively with colour, with algae-eating, with who knows what, but it’s everywhere and dynamic. I swim around, a poem comes to mind by a dead poet; he died too young on a foolish quest, but left a flow of words describing the world of fish with such an ease. Back in 1911, Rupert Brooke wrote,

In a cool curving world he lies

And ripples with dark ecstasies.

The kind luxurious lapse and steal

Shapes all his universe to feel

And know and be; the clinging stream

Closes his memory, glooms his dream,

Who lips the roots o' the shore, and glides

Superb on unreturning tides…

I’m not sure about ‘unreturning tides’, but here swim I in 2025, in the home of fish, which is more than a foreign land, it is a place I can never live. I feel invisible, wallowing around in my survival gear amongst the indigenous inhabitants, who are beautiful, weird, extraordinary, perhaps deadly and all unknown to me. I am not a fisherperson or a marine biology person or a boatie. I’m not that good at swimming as I was a childhood swimming lesson refuser, being too timid when left with my big sisters at the pool of a suntanned Mrs So-and-So, an old-school Aussie swimming teacher with little patience for over-sensitive children. She gave me a kickboard, barked orders at the others, and I never returned. The beach, however, a five-minute walk from home, was second nature to me. We came to an arrangement, the ocean waves and I, which has suited me ever since. Not having drowned, sixty-odd years after failing in the pool, I have come to Ningaloo to deepen my relationship with the salty seas and its population of other creatures.

Fish Like Painted Dreams

Parrot fish, like painted dreams, swim and nibble, swim and nibble, grazing the coral gardens with strangely fused teeth that scrape away all day long, keeping algae and sponges in check, ingesting bits of coral, and kindly excreting it as sand. Yes, they make sand from coral, a lot of it. They create beaches and small islands. This, I learn, is called bioerosion. Some of them are quite large. Gliding around, their beautiful skins are a palette of greens, blues, pinks and warm tones, with a gentle sheen. I later read, however, that some are plain whitish. It depends on their sex, which changes during their lifecycle. Apparently, they effortlessly change sex, like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, sans controversy, politics or medical intervention, just a fading of the colours to pale beige. They are clearly a vital part of the USFA. Without their incessant rasping and scraping and nibbling, the coral would be overwhelmed by algae and sponges and that would be the end of it. Parrot fish are the tireless maintenance crew, obsessed with cleaning up that coral. They would make good greenkeepers if they became human.

May blue damsel fish never grow pale. I am enchanted by them and want to swim close, which inevitably scatters them, momentarily. They seem to be held together by a magnetic force in friendship groups which move as one, bright as fairy lights, tiny as eyes, a flashing movement which one could follow to one’s doom. Their official name, Pomacentrus coelestis, is a distraction from the reality of these magical beings. For one thing, it’s too long for such a tiny creature, and working out the pronunciation is soooo left brain that it begs for dissection, a horrific fate to contemplate for such delightful little fishies. Hide, dear ones!

Drifting northwards, we glide over huge coral boulders called ‘bommies’. Gawking at the intricacies of reef-world, I observe corals that branch like leafless trees, brain-like corals with an intelligence of folds and cells, yet more corals like nothing I can compare them with, then a fluted clam shut wavy tight, its lips green with algae. I note the coming and going of fish who have places to go and things to do; well, I guess they do, but what would I know?

Diving down I peer into a cave where a school of medium-sized stripy fish just swim against the current, not going anywhere while constantly in smooth wiggly motion. It must be the fish equivalent of treading water, or running on a treadmill, and it’s mesmerizingly beautiful. I dive again and again to keep seeing them, for that’s all I can do, I have no role here. With curiosity and love, I gaze into a cave of fish going nowhere.

An Underwater Angel

Swimming over a sandy patch, I’m startled by the shape of a stingray resting on the sea floor. Partially covered in sand and motionless, its long, barbed tail spooks me and I swim away, returning after a while to sneak another look. Does it sleep? Does it sense me? Does it dream, or think, or intuit? I saw a leopard shark resting on the sea floor in the same way, static in the ever-moving waters, at home where it lies, no need for an address or a letterbox or bedroom. With unquestioned life membership of the USFA, these predators belong here more than I have ever belonged in my own home. All the other fish and associates are relaxed around them; I see no fear.

The menacing effect and stillness of the sleepy stingray contrasts with watching mighty manta rays barrel rolling a few days ago, off Coral Bay. We were on a dive trip. A spotter plane locates the rays, tells the skipper and the boat goes there. The group, donning snorkels, follows the guide off the back of the boat and into the USFA.

"The Underwater Society exists in a state of equilibrium. Everything lives side-by-side, minding its own business with occasional, quite specific, inter-species interaction."

Suddenly there it is: a huge, benign underwater angel, leathery wings fluidly undulating, wide-angle mouth permanently open, down near the sandy sea floor. It rolls over and over, ceaselessly tumbling, filter feeding on plankton-rich water, a pressurised flow of nutrient, while a collection of holidaying humans loiters above, staring downward, mesmerised. As the mantas roll, we see the markings on their tummies, like blotchy birthmarks. The markings are all unique. Scientists and dive guides use them to identify individuals, giving them names that foster a relationship, gently transcending the considerable barriers that divide people from such strange underwater beings. The mantas keep rolling. No farming, no violence, food miles or preparation are needed to sustain life, just swimming in a fun way, until they decide to move on, gliding out of focus to somewhere else.

Back in the boat, we are ecstatic when a pair of humpback whales come close, flashing tails, roundly diving and surfacing, spouting and waving, then gone. The Underwater Society exists in a state of equilibrium. Everything lives side-by-side, minding its own business with occasional, quite specific, inter-species interaction.

The manta rays are a case in point. One of them had a couple of fish attached to its underbelly. They were long and slender like silver arrows, with a sucker firmly stuck to the manta, who couldn’t care less. These sucker fish hitch a ride to save energy, hiding from predators and scrounging food scraps while providing minimal cleaning services to the manta, relieving them of time spent at cleaning stations. Having suckered on, the hitchhiking fish hang on for the ride as the manta tumbles like a ferris wheel. I wonder where they want to go, when do they decide to unhitch? What’s their story? There’s no David Attenborough commentary to enlighten me. There’s no talk, only being.

A word about cleaning stations, which is a concept confirming my opinion that the USFA is a highly sophisticated social system that takes care of everyone’s needs equally and intelligently. Cleaning stations are places where larger sea creatures come to be cleaned by smaller sea creatures. On reefs, specific coral bommies are the sites of such mutually beneficial businesses. A manta or shark or turtle or parrot fish visits the station, waiting their turn. It’s an exchange economy: small fry feed on parasites and dead skin that builds up on their larger neighbours. Our guides caution us to steer clear of the turtle and shark cleaning stations on our reef so as not to disturb them.

The Symbiotic Architecture Of The Underwater Society

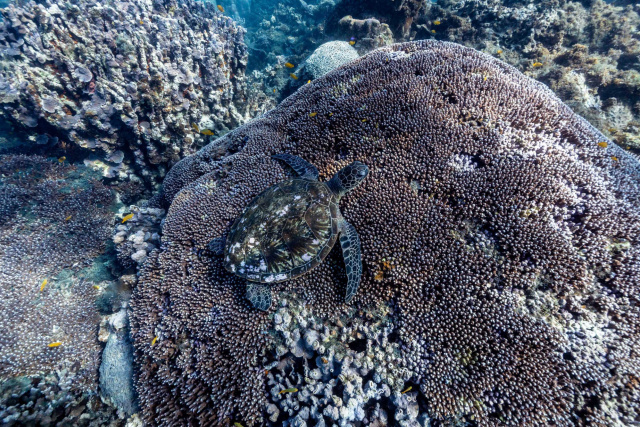

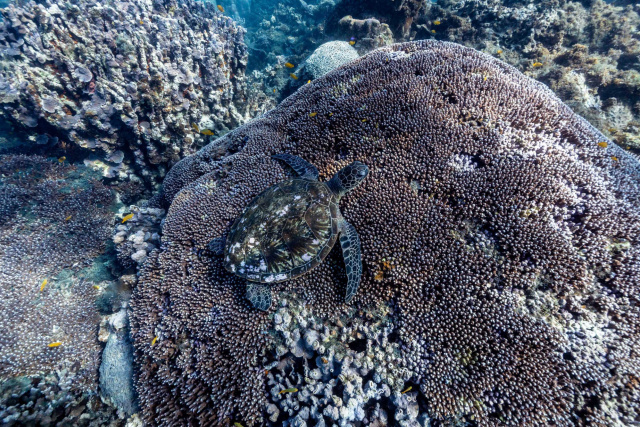

Back in the canyons, a sea turtle swims by so I follow it while I can, careful not to stray too far from our guide and our group. There’s another turtle resting on a rock in the deeps. Perhaps it’s a turtle cleaning station, or maybe it’s resting while waiting, as I don’t see any cleaning fish at work. Sea turtles can stay under for several hours at rest, less time when active. Some freshwater turtles stay under for a longer time by taking water in through their bottoms and somehow extracting the oxygen via a complexity of inner folds – here endeth my technical understanding!

The turtle on the rock, like the stingray and the leopard shark, is effortlessly still in the constant flow of currents. The quiet is penetrating, like deep meditation. Meanwhile, all the other fishies come and go with single-minded purpose, in clans or as individuals. The clans are collectives, segregated within the USFA. Segregation here is ok. Tribalism is de rigeur.

Little reef sharks cruise the canyons. After growing up at beaches where shark alarms sounded a frightening end to happy play in the waves, now I am a voyeur in their world. The word cute drifts into mind as I consider how to imprint the experience on my memory. Perhaps relatively cute is more to the point.

I want to hold these fleeting impressions, I want to internalise the knowledge of this experience in the USFA, I want to understand and feel myself as a neighbour from the land, not an alien from another universe.

I am struck by the sense of peace here. Nature documentaries depend on narratives of drama and suspense, played out in merciless predation, or weird life cycles, or competition for territory and copulation privileges. But on Ningaloo Reef, I experience the slow TV version. I witness calm, beauty, co-existence, acceptance and harmony. Fish and associates float, swim, rest, sleep, suspended always in the comforting salty sea, where coral provides homes, caves and food in the gloriously sumptuous, perfectly symbiotic architecture of the underwater society: here, everyone is equal and everyone has enough.

At Turquoise Bay, Tim and I swim together and apart, checking in with each other every so often, ensuring we don’t drift too far out, or too far north. We indicate things to each other, like the stingray, and the caves of fish, sharing the wonder and awe. We know how special and how brief is our time in the utopian society on Ningaloo, where all members live side-by-side, have what they need and there is no fussing or bothering about rights or power or governance.

Finally, we reach the northern buoy and make our way to the shore. I linger in the shallows, at the edge, in the transition zone, not wanting to leave the USFA, knowing I am an uninvited guest whose presence is meaningless to all but myself. Grains of sand sneak into my flippers and wetsuit, excreted by parrot fish.

I know we may never return, and I know about an evil stalking the realm of the USFA. It haunts our joy and breaks our hearts. The threat is not sharks or stingrays, predatory sea birds or any creature of the deep or shallow. It’s warming water. The spectre of coral bleaching chills our brains. Although this reef has been spared for now, other parts of Ningaloo Reef died last summer.

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow will come, soft currents circulating in the heating oceans, leaving white graveyards where once the USFA eternally rested and swam in the canyons of coral, just being.

Helen Cushing

Freerange Journalist

A Parallel Universe

In it.

Suspended.

Adrift in a watery immensity.

Apparently accepted by the Underwater Society, whose members take no notice of us, we are snorkellers, quite an abundance of snorkellers, on a tourism mission, superficially at least.

A fringing reef such as Ningaloo is a coveted destination despite being remoter than most remote places on the planet. Remote here means 1,300 kilometres north of the remotest city in the world, which is Perth, Western Australia. Western Australia is enormous, mostly desert, full of startling geology, a multitude of unique plants and dens of hyper capitalism in the form of mines. I have visited a few choice pockets, where the geology and the plants and the vastness have coalesced in a magical formula equalling awe and wonder. The coastline is an extravagant 12,889 kilometres long, not counting islands: infinite scope for beauty, wildness and wayfinding.

Here I am, finding my way in the Cape Range National Park, a rugged peninsula where sprawling suburbs of red earth termite mounds populate the desiccated plains against the backdrop of a squat plateau, arid, unforgiving, cracked with shadowy gorges where rock wallabies and lizards shelter, while raptors drift like little clouds on currents of air, sweeping the sky, lazy and alert at the same time, seeing more than all the tourism efforts below reveal.

Evolving Into A Sea Creature

I am not adapted for underwater exploration, being of an earthy disposition. I love gardening, for example, and walking. For this moment I need evolutionary help. I need a new skin and webbed feet; I need a breathing tube and eye protection. The national park visitor’s centre has the answer, skipping millennia of genetic mutation. I hire a wetsuit, flippers, mask and snorkel – evolving into a sea creature costs $40 for two days.

Leading off the main artery, the peninsula is striated with short roads ending in car parks that feed you into walking tracks which in turn, deliver you to beaches, bays, rock platforms, fruit bats dangling in mangroves, lagoons, a bird hide, a turtle nesting site. Other short roads end with basic camping sites where tents have become a rare and endangered species, dwarfed by over-equipped mobile homes in denial about the notion of ‘basic’.

Having wrestled bodies into wetsuits in the Turquoise Bay carpark, Tim and I head to the beach, pilgrims from a faraway island lapped by the Southern Ocean, seeking absolution from the evils of our modern world, from news of wars and melting glaciers, extinctions and extractions, coral bleaching and immoral tyrannies, the daily diet of terror which lays waste our souls. Here, we will feed on something pure that should sustain us for a while when we return to buildings, carbon emissions, razed forests and farmed fields of poison.

The beach is peopled with fellow pilgrims, co-existing with mutual purpose. A toddler in a huge bucket at the seashore is contented in her own contained ocean. A tour group receives instructions from their guide. Face-down, bodies move around out there in the water, which laps around them with indifference, making room for everyone equally. The sun is watching, there are no clouds, a wind blows; it practically always blows.

"Here, we will feed on something pure that should sustain us for a while when we return to buildings, carbon emissions, razed forests and farmed fields of poison."

All Is Contained In The Massaging Sea

We walk south along the beach, that we may drift north with the current, among canyons of coral in the land of the USFA. Kitted out, we launch in. White sand and ripples, then dark patches of other stuff, and a few fish cruising these shallow outskirts before the reef proper. They know the way to somewhere meaningful I guess, or are they outliers pushing fluid boundaries because they can? Perhaps they are introverts who find reef society overcrowded, preferring some emptiness.

It’s so peaceful under water, where no-one talks and all is contained in the massaging sea.

My flippering feet push me beyond the shallows where fish society is busy on the reef, lively with colour, with algae-eating, with who knows what, but it’s everywhere and dynamic. I swim around, a poem comes to mind by a dead poet; he died too young on a foolish quest, but left a flow of words describing the world of fish with such an ease. Back in 1911, Rupert Brooke wrote,

In a cool curving world he lies

And ripples with dark ecstasies.

The kind luxurious lapse and steal

Shapes all his universe to feel

And know and be; the clinging stream

Closes his memory, glooms his dream,

Who lips the roots o' the shore, and glides

Superb on unreturning tides…

I’m not sure about ‘unreturning tides’, but here swim I in 2025, in the home of fish, which is more than a foreign land, it is a place I can never live. I feel invisible, wallowing around in my survival gear amongst the indigenous inhabitants, who are beautiful, weird, extraordinary, perhaps deadly and all unknown to me. I am not a fisherperson or a marine biology person or a boatie. I’m not that good at swimming as I was a childhood swimming lesson refuser, being too timid when left with my big sisters at the pool of a suntanned Mrs So-and-So, an old-school Aussie swimming teacher with little patience for over-sensitive children. She gave me a kickboard, barked orders at the others, and I never returned. The beach, however, a five-minute walk from home, was second nature to me. We came to an arrangement, the ocean waves and I, which has suited me ever since. Not having drowned, sixty-odd years after failing in the pool, I have come to Ningaloo to deepen my relationship with the salty seas and its population of other creatures.

Fish Like Painted Dreams

Parrot fish, like painted dreams, swim and nibble, swim and nibble, grazing the coral gardens with strangely fused teeth that scrape away all day long, keeping algae and sponges in check, ingesting bits of coral, and kindly excreting it as sand. Yes, they make sand from coral, a lot of it. They create beaches and small islands. This, I learn, is called bioerosion. Some of them are quite large. Gliding around, their beautiful skins are a palette of greens, blues, pinks and warm tones, with a gentle sheen. I later read, however, that some are plain whitish. It depends on their sex, which changes during their lifecycle. Apparently, they effortlessly change sex, like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, sans controversy, politics or medical intervention, just a fading of the colours to pale beige. They are clearly a vital part of the USFA. Without their incessant rasping and scraping and nibbling, the coral would be overwhelmed by algae and sponges and that would be the end of it. Parrot fish are the tireless maintenance crew, obsessed with cleaning up that coral. They would make good greenkeepers if they became human.

May blue damsel fish never grow pale. I am enchanted by them and want to swim close, which inevitably scatters them, momentarily. They seem to be held together by a magnetic force in friendship groups which move as one, bright as fairy lights, tiny as eyes, a flashing movement which one could follow to one’s doom. Their official name, Pomacentrus coelestis, is a distraction from the reality of these magical beings. For one thing, it’s too long for such a tiny creature, and working out the pronunciation is soooo left brain that it begs for dissection, a horrific fate to contemplate for such delightful little fishies. Hide, dear ones!

Drifting northwards, we glide over huge coral boulders called ‘bommies’. Gawking at the intricacies of reef-world, I observe corals that branch like leafless trees, brain-like corals with an intelligence of folds and cells, yet more corals like nothing I can compare them with, then a fluted clam shut wavy tight, its lips green with algae. I note the coming and going of fish who have places to go and things to do; well, I guess they do, but what would I know?

Diving down I peer into a cave where a school of medium-sized stripy fish just swim against the current, not going anywhere while constantly in smooth wiggly motion. It must be the fish equivalent of treading water, or running on a treadmill, and it’s mesmerizingly beautiful. I dive again and again to keep seeing them, for that’s all I can do, I have no role here. With curiosity and love, I gaze into a cave of fish going nowhere.

An Underwater Angel

Swimming over a sandy patch, I’m startled by the shape of a stingray resting on the sea floor. Partially covered in sand and motionless, its long, barbed tail spooks me and I swim away, returning after a while to sneak another look. Does it sleep? Does it sense me? Does it dream, or think, or intuit? I saw a leopard shark resting on the sea floor in the same way, static in the ever-moving waters, at home where it lies, no need for an address or a letterbox or bedroom. With unquestioned life membership of the USFA, these predators belong here more than I have ever belonged in my own home. All the other fish and associates are relaxed around them; I see no fear.

The menacing effect and stillness of the sleepy stingray contrasts with watching mighty manta rays barrel rolling a few days ago, off Coral Bay. We were on a dive trip. A spotter plane locates the rays, tells the skipper and the boat goes there. The group, donning snorkels, follows the guide off the back of the boat and into the USFA.

"The Underwater Society exists in a state of equilibrium. Everything lives side-by-side, minding its own business with occasional, quite specific, inter-species interaction."

Suddenly there it is: a huge, benign underwater angel, leathery wings fluidly undulating, wide-angle mouth permanently open, down near the sandy sea floor. It rolls over and over, ceaselessly tumbling, filter feeding on plankton-rich water, a pressurised flow of nutrient, while a collection of holidaying humans loiters above, staring downward, mesmerised. As the mantas roll, we see the markings on their tummies, like blotchy birthmarks. The markings are all unique. Scientists and dive guides use them to identify individuals, giving them names that foster a relationship, gently transcending the considerable barriers that divide people from such strange underwater beings. The mantas keep rolling. No farming, no violence, food miles or preparation are needed to sustain life, just swimming in a fun way, until they decide to move on, gliding out of focus to somewhere else.

Back in the boat, we are ecstatic when a pair of humpback whales come close, flashing tails, roundly diving and surfacing, spouting and waving, then gone. The Underwater Society exists in a state of equilibrium. Everything lives side-by-side, minding its own business with occasional, quite specific, inter-species interaction.

The manta rays are a case in point. One of them had a couple of fish attached to its underbelly. They were long and slender like silver arrows, with a sucker firmly stuck to the manta, who couldn’t care less. These sucker fish hitch a ride to save energy, hiding from predators and scrounging food scraps while providing minimal cleaning services to the manta, relieving them of time spent at cleaning stations. Having suckered on, the hitchhiking fish hang on for the ride as the manta tumbles like a ferris wheel. I wonder where they want to go, when do they decide to unhitch? What’s their story? There’s no David Attenborough commentary to enlighten me. There’s no talk, only being.

A word about cleaning stations, which is a concept confirming my opinion that the USFA is a highly sophisticated social system that takes care of everyone’s needs equally and intelligently. Cleaning stations are places where larger sea creatures come to be cleaned by smaller sea creatures. On reefs, specific coral bommies are the sites of such mutually beneficial businesses. A manta or shark or turtle or parrot fish visits the station, waiting their turn. It’s an exchange economy: small fry feed on parasites and dead skin that builds up on their larger neighbours. Our guides caution us to steer clear of the turtle and shark cleaning stations on our reef so as not to disturb them.

The Symbiotic Architecture Of The Underwater Society

Back in the canyons, a sea turtle swims by so I follow it while I can, careful not to stray too far from our guide and our group. There’s another turtle resting on a rock in the deeps. Perhaps it’s a turtle cleaning station, or maybe it’s resting while waiting, as I don’t see any cleaning fish at work. Sea turtles can stay under for several hours at rest, less time when active. Some freshwater turtles stay under for a longer time by taking water in through their bottoms and somehow extracting the oxygen via a complexity of inner folds – here endeth my technical understanding!

The turtle on the rock, like the stingray and the leopard shark, is effortlessly still in the constant flow of currents. The quiet is penetrating, like deep meditation. Meanwhile, all the other fishies come and go with single-minded purpose, in clans or as individuals. The clans are collectives, segregated within the USFA. Segregation here is ok. Tribalism is de rigeur.

Little reef sharks cruise the canyons. After growing up at beaches where shark alarms sounded a frightening end to happy play in the waves, now I am a voyeur in their world. The word cute drifts into mind as I consider how to imprint the experience on my memory. Perhaps relatively cute is more to the point.

I want to hold these fleeting impressions, I want to internalise the knowledge of this experience in the USFA, I want to understand and feel myself as a neighbour from the land, not an alien from another universe.

I am struck by the sense of peace here. Nature documentaries depend on narratives of drama and suspense, played out in merciless predation, or weird life cycles, or competition for territory and copulation privileges. But on Ningaloo Reef, I experience the slow TV version. I witness calm, beauty, co-existence, acceptance and harmony. Fish and associates float, swim, rest, sleep, suspended always in the comforting salty sea, where coral provides homes, caves and food in the gloriously sumptuous, perfectly symbiotic architecture of the underwater society: here, everyone is equal and everyone has enough.

At Turquoise Bay, Tim and I swim together and apart, checking in with each other every so often, ensuring we don’t drift too far out, or too far north. We indicate things to each other, like the stingray, and the caves of fish, sharing the wonder and awe. We know how special and how brief is our time in the utopian society on Ningaloo, where all members live side-by-side, have what they need and there is no fussing or bothering about rights or power or governance.

Finally, we reach the northern buoy and make our way to the shore. I linger in the shallows, at the edge, in the transition zone, not wanting to leave the USFA, knowing I am an uninvited guest whose presence is meaningless to all but myself. Grains of sand sneak into my flippers and wetsuit, excreted by parrot fish.

I know we may never return, and I know about an evil stalking the realm of the USFA. It haunts our joy and breaks our hearts. The threat is not sharks or stingrays, predatory sea birds or any creature of the deep or shallow. It’s warming water. The spectre of coral bleaching chills our brains. Although this reef has been spared for now, other parts of Ningaloo Reef died last summer.

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow will come, soft currents circulating in the heating oceans, leaving white graveyards where once the USFA eternally rested and swam in the canyons of coral, just being.

You might like...

From surfing came a love of the ocean

The fascinating beaches of Bruny

The Story of Kowai Bush and the Mears Track

Somewhere Along the South Cape Bay Track

Newsletter

Sign up to keep in touch with articles, updates, events or news from Kuno, your platform for nature